The other day, I mentioned to a friend that I’d enjoyed a pleasant Pinot Grigio with dinner the previous evening. “It that red wine?” he asked innocently. Initially I was slightly taken aback, but it’s easy to understand why people get mixed up over Pinot grapes. There are dozens of them with the word Pinot (PEE-noh) in the name, so if you get your Pinots confused you are almost certainly not alone. However, only four of them are important, so it’s not much of a challenge to remember their names.

The first written record of “pinot” first appeared around 1375 and we can be pretty sure that the grape was around for a good many years previously. It’s thought that the name probably comes from the fact that the small, tightly-packed grape clusters resemble pine cones.

The Leader of the Pack and the most famous of the four is undoubtedly Pinot Noir (PEE-noh NWAH), a grape that produces relatively light-bodied and fruity wine.

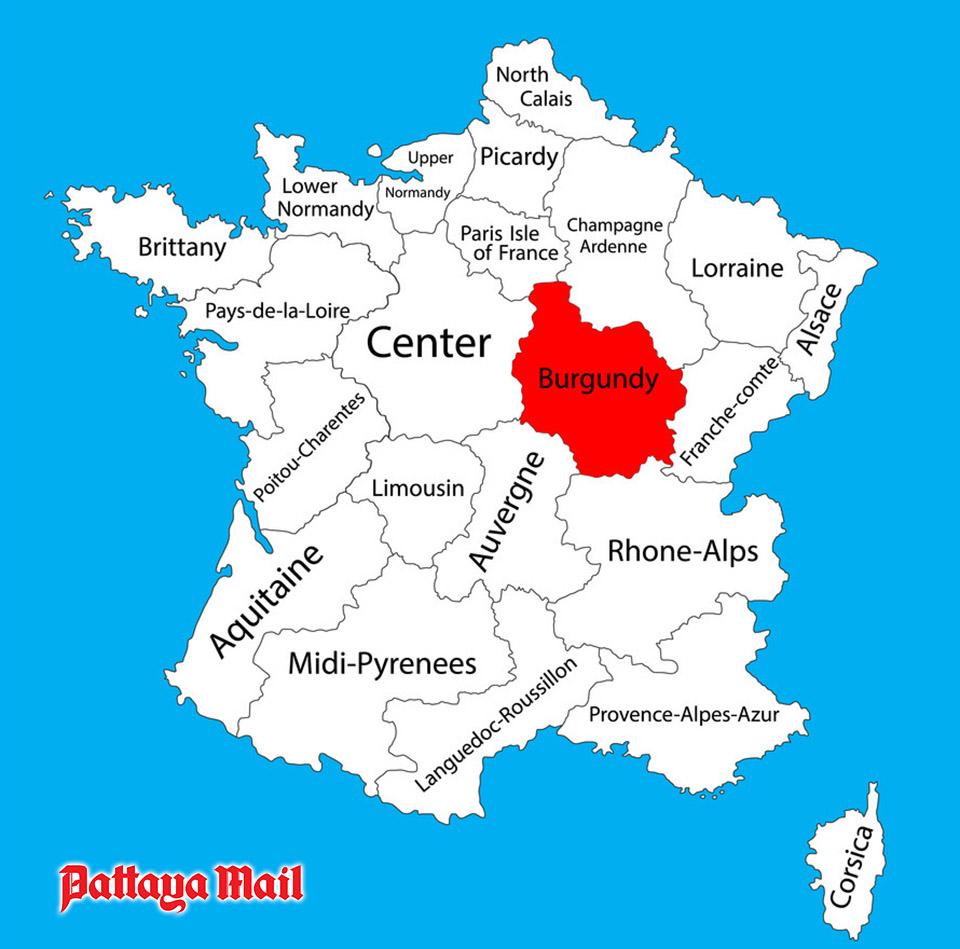

Although the name means “black pinot”, the young grapes are a pinkish colour and develop into a distinctive dark blue. I’ve always had a passion for Pinot Noir, ever since I had the opportunity to taste some of the splendid reds of Burgundy. In that region, Pinot Noir finds its greatest and finest expression. Even the name “Burgundy” has a sonorous, commanding quality: a kind of resplendent grandeur. The province is in east-central France and from the 11th to 15th centuries, it was home to the Dukes of Burgundy. The capital, Dijon, was a wealthy and powerful city and a major European centre of art and science. Burgundy was a focal point of courtly culture that set the fashion for European royal houses and their courts.

The astonishing wealth in Burgundy allowed the development of vineyards and viticulture. Pinot Noir was the only red grape permitted in the region and it thrived there. The loving care bestowed on the Burgundian vineyards over many generations enabled the production of some of the finest red wines the world has ever seen. The same could be said of the white wines of Burgundy, nearly all of which are made from Chardonnay. Today, Pinot Noir is grown in many countries including Australia and New Zealand and it’s also used in the making of Champagne. However, this grape variety can be tricky to cultivate and the yields are rather low, which is why wines made from Pinot Noir tend to be more expensive than other varietals.

The second most important Pinot is the “Pinot Gris” (PEE-noh GREE). This variety makes white wine only and has been known since the Middle Ages. The grapes usually have a pinkish-grey hue, accounting for the name, but the colours can vary from blue-grey to pink-brown. In Italy, the grape is known as Pinot Grigio (PEE-noh GREE-joh).

Although the grape is the same, Pinot Gris and Pinot Grigio can taste dramatically different. Pinot Gris from the Alsace region of France makes rich, aromatic, full-bodied wines. The Italian version has a clean profile of apple and pear with an emphasis on bright acidity. Wine from other countries is either labelled Pinot Gris or Pinot Grigio depending on the style.

Thirdly, Pinot Blanc is found mainly in France and popular in Alsace but also grown in Germany, Luxembourg, Italy, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia and produces a full-bodied white wine. In Germany, Pinot Banc known as Weißer Burgunder or Weißburgunder.

Finally, we have the dark red Pinot Meunier (“Miller’s Pinot”) which is one of the most widely-planted grapes in France because it’s used in the making of Champagne. It is rarely seen as a single varietal except in Germany, where it’s known (somewhat confusingly) as Schwarzriesling and is used to make simple red wines with a fresh, fruity and slightly “jammy” character.

And that’s basically it: Pinot Noir (red), Pinot Gris/Pinot Grigio (white), Pinot Blanc (white) and Pinot Meunier (red). You may be wondering whether these “pinot” grapes are related to each other in some way. Well, yes, they are. They are from the same family (or “cultivar” to be more technically accurate) and because this family is so ancient, it has had centuries to mutate into new clones. The word “clone” comes from the Greek word for “twig” and refers to the age-old practice of propagating new vines by taking cuttings and grafting. It probably acquired its slightly sinister tone in more recent years due to artificial cloning. The process often happens naturally when a cell replicates itself without any genetic alteration or recombination. And of course, bacteria create genetically identical duplicates of themselves. Oh dear, my mind is starting to wander. Let’s try the wine.

Heritage Road Moonstone Pinot Grigio 2023 (white), Australia ฿469 @ Villa

This is one of many brands from Australian Vintage Ltd, a massive company that also handles well-known products such as McGuigan Wines, Tempus Two and Barossa Valley Wine Company. “Quality, consistency and value, along with ongoing and sustained international recognition,” says their website, “has resulted in our brands enjoying excellent growth globally. We were awarded Wine Company of the Year by Winestate Magazine in 2022 for the fifth year running.” The company owns and leases vineyards in major wine producing regions across Australia with 2,600 hectares (about 6.5 thousand acres) under vine.

Their Buronga Hill Winery in southern NSW is the third largest winery by capacity in Australia and equipped with state-of-the-art winemaking technology. The site is at the forefront of sustainable winemaking and has seen major investments in solar energy, including its own large-scale solar plant.

This is an entry-level wine: at this price it can be nothing else. But even this basic wine shows the characteristic qualities of the grape in terms of aroma, colour and taste. It’s light and refreshing and reflects the qualities of its Italian cousins. With a pale gold hue, it has a delicate citrus and honeysuckle aroma along with a dash of yeast which drifts away when the bottle has been open for a time. The attractive yeasty aroma is not a fault. It’s known as an autolytic aroma because it’s the result of yeast autolysis; a chemical reaction between the wine and the extinguished yeast cells. You often find this aroma in white wine which has been left to ferment “on the lees”, a technique often used to impart a rich and creamy quality to the wine.

You can see from the vintage year that this is a remarkably young wine. But it’s none the worse for that. The grapes would have been harvested sometime between February and April 2023. So not surprisingly, this is a light-bodied wine. It’s fairly dry with reminders of citrus and honey on the palate. There’s also an attractive tingle of acidity and a lingering long finish. At an easy-to-drink 11.0 °C this is an attractive simple wine which would make a delightful aperitif but it would also well with light chicken or fish dishes. It would work well with many Thai-style dishes too.

The reference to “Moonstone” on the label puzzled me at first. Perhaps the word is a ploy to impart a touch of magic and mystery. The name Moonstone derives from the polished stone’s characteristic and unique visual effect – a kind of milky, bluish interior light. In its gemstone form, this fragile stone was popular in ancient Roman jewelry and has always been a sacred stone in India where it’s a traditional wedding gift. It was also a popular choice for jewelers during the Art Nouveau period. In Europe, it was believed that Moonstone could cure sleeplessness. Perhaps this wine can do much the same thing, if you drink enough of it.