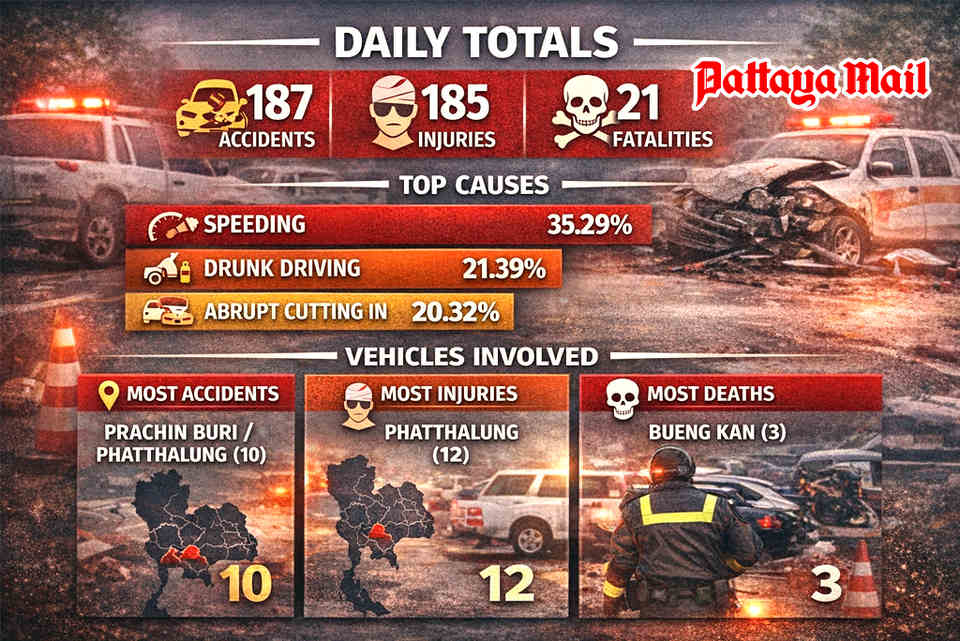

BANGKOK, Thailand – Every year, Thailand enters what is officially known as the “Seven Dangerous Days.” As a lawyer practicing in Pattaya, I have learned to hear that phrase with a sense of quiet unease not because it is inaccurate, but because of how easily it is accepted. After four days of this year’s holiday period, the figures tell a familiar story. In a single day, authorities recorded 187 road accidents, 185 injuries, and 21 fatalities. These are not abstract numbers to those of us who work in law. Behind them are insurance disputes, criminal proceedings, compensation claims, and families suddenly forced to navigate a legal system at the worst moment of their lives.

The causes are well known. Speeding accounts for more than a third of accidents. Drink-driving follows closely, despite repeated warnings that penalties are severe and insurance coverage may be voided. Abrupt lane cutting often dismissed as routine impatience ranks alarmingly high. From a legal perspective, none of this is ambiguous. The risks are established, the laws are clear, and the consequences are foreseeable.

Motorcycles remain the most exposed, involved in nearly three-quarters of all accidents. This is not merely a matter of personal choice; it reflects economic reality. Motorcycles are the primary means of transport for millions, yet they offer the least protection and, in many cases, the weakest insurance coverage. When accidents occur, the legal and financial fallout often extends far beyond the rider alone.

Geographically, the pattern is equally predictable. Prachin Buri and Phatthalung recorded the highest number of accidents, with Phatthalung also leading in injuries. Bueng Kan saw the highest number of fatalities. These outcomes are shaped by road design, enforcement capacity, and travel density factors that are structural, not accidental.

From my professional experience, enforcement alone is not the problem. Police checkpoints, breath tests, and speed controls are necessary, and they do save lives. But they are reactive tools, deployed during holidays and then quietly scaled back. The deeper issue is that Thailand continues to treat road safety as a seasonal concern rather than a permanent policy priority.

The phrase “Seven Dangerous Days” itself reveals the problem. It frames mass casualties as something to be managed rather than prevented. In legal terms, when harm is foreseeable and repeated, it ceases to be an accident and becomes a systemic failure. What is missing is accountability beyond the driver. Road design standards, vehicle safety regulation, insurance enforcement, and consistent year-round policing all play a role. Yet public discussion rarely moves beyond individual blame, even though the data shows the same patterns year after year.

As a lawyer, I see the aftermath long after the headlines fade. Compensation cases that take years. Families who never fully recover financially or emotionally. Foreign residents and tourists who assume insurance will protect them, only to discover exclusions they never understood.

Until Thailand is willing to move beyond the language of “dangerous days” and confront road safety as a structural legal and policy issue, the outcome will remain unchanged. The travel will continue. The warnings will be repeated. And the statistics will arrive on schedule just as they always do.