A full house of enthusiastic guests at Ben’s Theater in Jomtien recently welcomed three talented young musicians from Bangkok to give the last performance of the season. They were Pattapol Jirasuttisarn (violin) Kunut Chaloempornpong (cello) and pianist Anant Changwaiwit who performed two of the most well-known works from the piano trio repertoire. Although Anant has appeared previously at Ben’s on several notable occasions, it was the first appearance in Jomtien for Pattapol and Kunut. It was a magnificent performance too, with a remarkably high technical and musical standard which also seemed to catch the character and spirit of the music.

Mendelssohn’s Piano Trio No 1 in D minor, Op 49 is one of the composer’s most popular chamber works and was written when he was thirty and already a well-known name in the musical world having travelled extensively in Europe. Several years earlier, while staying in Paris in 1832, Mendelssohn wrote a letter to his sister Fanny and told her about a piano trio he had in mind, in which the piano would take a more active role in relation to the violin and cello. The Piano Trio No 1 was the result. Mendelssohn took the advice of his life-long friend, the German composer, conductor and pianist Ferdinand Hiller and revised the piano part. The revised version was even more virtuosic and romantic in style than the original. At the first performance in 1840, only the violinist and cellist had instrumental parts. Mendelssohn, who was playing the piano, had to play the entire work from memory. Schumann loved the work and on one occasion declared Mendelssohn to be “the Mozart of the nineteenth century.” Praise indeed; especially coming from the critical and depressive Robert Schumann.

The work begins mysteriously with a lyrical cello solo accompanied by piano chords, but the quiet mood soon gives way to passionate and powerful music which typifies the work. As the composer intended, the piano dominates throughout the work with technically-challenging, virtuosic writing. Pianist Anant Changwaiwit took the difficult part in his stride and provided a thrilling performance. The second movement was beautifully timed with near-perfect instrumental balance and fine string playing from Pattapol and Kunut. I was impressed with the warm string tone and the spot-on intonation throughout the concert. The third movement is a scherzo and while perhaps not quite as light-footed as the composer may have wanted, it contained some fine playing and brilliant piano figurations, splendidly and confidently played by Anant. This movement goes at quite a pace and quite a challenge to hold the ensemble together at this tempo. Due to their relative positions on the stage, the pianist and violinist were unable to have direct eye-contact and at times, the playing was not always together. However, the ensemble was much improved in the Finale. The composer made extensive revisions to this movement and the players gave a splendid performance, with some lovely cello solo playing from Kunut. The audience clearly appreciated the performance, judging by the thunderous applause at the end.

Of course, all three musicians have had years of experience. Kunut Chaloempornpong for example, began studying the cello at the age of eleven and eventually studied at the Conservatory of Music at Rangsit University. He later attended the Royal Conservatory of Brussels and has played in the Royal Bangkok Symphony Orchestra, the Asian Youth Orchestra, the Bangkok Metropolitan Orchestra and Siam Sinfonietta. He has been the principal cellist of the Thai Youth Orchestra and Princess Galyani Vadhana Youth Orchestra and taken part in festivals in the USA, Europe and Asia.

Violinist Pattapol Jirasuttisarn also studied abroad. He began violin lesson at the age of six and later went to the College of Music at Mahidol University. He became a full-time member of Thailand Philharmonic Orchestra and then moved to Europe to study at the Hochschule für Musik, Detmold, Germany. He gained his Master’s Degree in Violin Performance and Creativity at the Musikhochschule, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität in Münster. He has played with several German orchestras and has performed in numerous other countries such as Japan, New Zealand and Hungary.

Pianist Anant Changwaiwit is in great demand and has performed numerous piano concertos both in Thailand and abroad. He has frequently appeared in concerts and festivals with artists from Europe, USA and Asia and holds a Bachelor’s degree in Classical Music Performance from the College of Music, Mahidol University.

Concert-goers often don’t realise the amount of time, energy and practising that is necessary for musical performance. For example, all three musicians began musical studies in their childhood and worked continuously for many years to reach their present standard. In music, practising time is measured in hours per day and every musician, however talented, requires several hours of daily practice. Every concert requires extensive rehearsal time too. The two works performed at the recent concert amount to about seventy minutes of music. Anant told me that the three of them had organised four rehearsals each of two hours; a total of about eight hours rehearsal time.

These extensive rehearsals showed in the remarkable standard of the performance, especially in Dvořák’s Piano Trio No 4 in E minor, Opus 90 which was played in the second half of the concert.

I came across this wonderful work as a music student a good many years ago and have always admired it. It was one of my mother’s favourites too. Over the years, I’ve heard it many times and I could probably sing most of it from memory, though few people would want to hear me try. I was especially interested to hear what the young musicians from Bangkok would make of it. I can only say that their performance was brilliant and reached heights of emotion that surprised even me. The members of the trio had clearly given the work a great deal of thought.

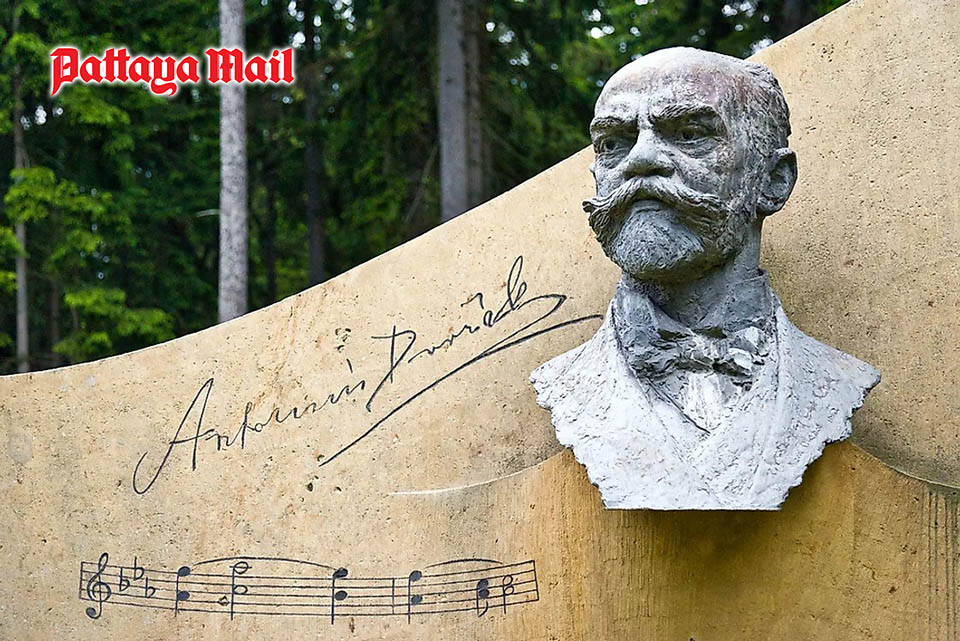

It is popularly known as the “Dumky” Trio. The word dumky is the plural of dumka; a word borrowed from the Ukrainian which literally means “thought”. It gradually came to mean an epic ballad, invariably melancholic in character. The musical dumka is a piece which contrasts slow, dreamy sections with more lively and boisterous ones. Using the dumka as a format gave Dvořák (dvor-jzahk) a perfect opportunity to break away from the traditional chamber music forms and stamp the work with genuine Bohemian character. There are six movements, each using a dumka of a different mood and style. He completed the work in February 1891 and it was first performed the following April with Dvořák himself playing the piano part. It was so well received that the composer played it at each of the forty concerts on his farewell tour of Moravia and Bohemia before he left for an extended stay in the United States.

The sudden changes of mood that typify the dumka create challenges for the performers who have to change the musical mood rapidly. It is not an easy piece to bring off successfully. But the three players really caught the magic in the first movement with some passionate playing. The opening cello passage was superbly played by Kunut and followed by a lovely string passage in which Kunut and Pattapol blended their string sounds beautifully. The quick middle section was brilliant, with sparkling piano work from Anant and excellent ensemble.

The second movement was, for me at least, one of the highlights of the evening: beautifully “paced” chords from the piano at the start and delightful pianissimo string playing that captured the almost religious feeling of the opening. There was splendid dynamic control especially in the spikey middle section. The closing section, which is similar to the beginning, was intensely moving, as were the opening bars of the third movement. They contain a single unaccompanied melody on the piano. It looks easy on paper, but quite another matter giving it musical meaning, which Anant certainly did. Dvořák wrote some wonderful melodies for the cello and the movement featured yet another lovely expressive cello solo from Kunut. I especially enjoyed the clean and defined violin tone quality from Pattaporn. The closing section of the movement was sheer magic and another musical highlight.

The fluid tempo changes in the fourth movement were well executed and the excellent timing of the ensemble really seemed to catch the Bohemian spirit of the music. The players launched into the fifth movement with great style and performed it with excellent precision and excellent articulation from the strings. The finale, which contrasts mysterious reflective sections with a kind of stomping Bohemian country dance brought the work to a heroic close. I think what impressed me most was the sheer musicality of the performance. It was technically superb but the players brought that little bit extra: that indefinable quality that imbues the music with joy, elation and magic. Anant, Pattapol and Kunut gave one of the most expressive and sensitive performances I have heard recently, in which lively, spirited playing was contrasted with moments of profound sublimity.