Mozart evidently once commented to the German piano maker Johann Andreas Stein, “To my eyes and ears, the organ will ever be the King of Instruments.” Honoré Balzac, the psychologically-tangled French novelist was equally enthusiastic and wrote, “The organ is the grandest, the most daring, the most magnificent of all instruments invented by human genius.” Well, I don’t know about you, but I cannot share Mozart’s or Balzac’s passion for pipe organs. Neither could my mother, who was a competent pianist. “The sound of a church organ leaves me cold”, she always used to say. I inherited her indifference to the instrument, so it must have been in a moment of utter madness that I decided to have organ lessons.

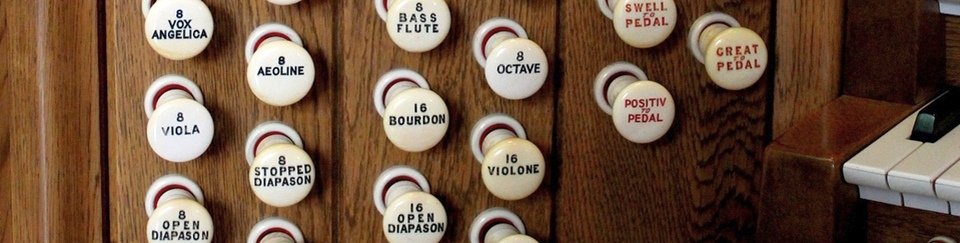

At the time, I was at music college and because I’d already gained diplomas in cello and theory, the organ seemed an interesting challenge. My initial eagerness didn’t last. My teacher was a well-known London organist, but he struck me as a slightly tetchy, irascible individual. He was not impressed by my organ playing because I was completely useless. You see, an organist must deal with multiple keyboards, lots of controls known as “stops” and a pedal board on which you play the bass part with your feet. I simply couldn’t get the hang of the wretched thing and anyway, I despised the wheezing, disembodied sound it made. I could manage simple pieces, but to play a challenging Bach fugue you need more footwork skills than an Irish dancer. I had a better chance of flying to the moon on the back of a goose.

Mind you, I had tried. I had tried desperately. During the long summer holidays, I would return to the family home on the grey rocky island in Wales and every couple of days I would practise the organ at a Welsh chapel on the outskirts of town. I had to collect the chapel’s front door key from the caretaker’s wife, a heavy, ornate thing worn down by years of use. The key I mean, not the caretaker’s wife. The chapel was a grey forlorn place, the sight of which filled me with foreboding. Even under the cold sunlight of our northern home, the inside of the chapel spoke of gloom and despondency.

It was one of the most joyless places I can remember. How different the mood, years later when I visited the fabulous Notre Dame in Paris, a wonderful building that exuded light, magic and mysticism. Simply being inside Notre Dame raises one’s spirits and brings a sense of elation and wonderment. Not so the Welsh chapel, in which unseen rats scurried among the rafters and the air hung with the musty, earthy odour of decaying hymn books. It was a scary, disquieting place which oozed misery. I wouldn’t have been surprised to see the spectre of some long-deceased local resident floating among the pews.

The organ loft, which contained the keyboards and the inevitable selection of knobs and pedals was a tiny, cluttered space. Even the dusty wooden rear stairway into the loft induced in me a profound feeling of despair. After about two hours practising in this Stygian gloom, I’d had enough. And probably so had the rats. This routine continued throughout the weeks of the summer holiday. One day, in the middle of something by Frescobaldi, I suddenly saw the light. I stopped playing and asked myself, “Whatever am I doing this for?” There was no answer. The activity, for me at least, was completely pointless.

There was no need to suffer this hateful drudgery when I could be outside enjoying the summer. I instantly decided that my brief affair with the organ was over. I would become dis-organized. As far as I was concerned, the organ could go to hell and so could my cheerless teacher. I packed up my music, returned the chapel key to the caretaker’s wife and never returned. As it turned out, life had other plans, and was not prepared to let me escape the organ so easily.

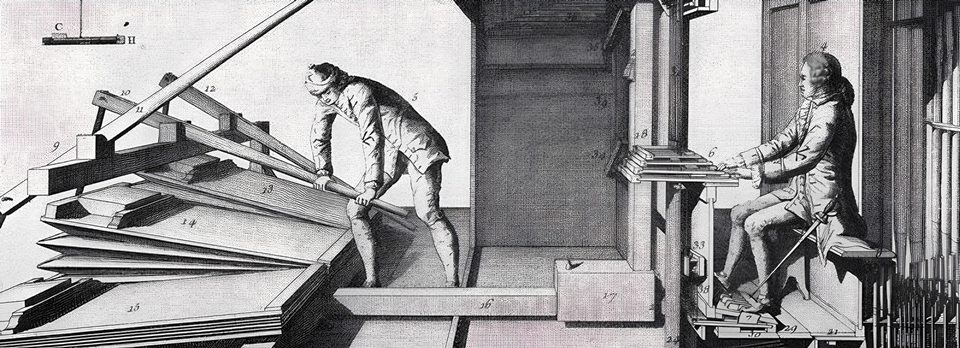

You probably know that the organ produces it’s sound by air pushed through the pipes. Each pipe produces a single tone and the pipes are arranged in sets called “ranks”. Most organs have many ranks of pipes and the player can select various combinations by using controls called “stops” creating a variety of tone colours. The instrument usually has several keyboards as well as a pedal-board played by the feet. The pipe organ is one of the oldest musical instruments and can be dated back to an invention called the hydraulis, created in Alexandria around 246BC by a Greek engineer named Ctesibius. It was intended to demonstrate the principles of hydraulics rather than a means of creating sounds, and it wasn’t used as a musical instrument until well over a hundred years later. In Roman times, simple pipe organs were used in theaters, amphitheaters and at banquets. The Roman Emperor Nero named it as his favourite musical instrument.

Ironically, the early Christian church was cautious about using musical instruments in worship and it wasn’t until around 900AD that small pipe organs began to appear in places of worship. During the Middle Ages, organs spread throughout Europe and by the early Renaissance they were well-established in monastic churches. The first organs at the cathedral in Winchester and Notre Dame of Paris date from this period. Because of its ability to play sustained sounds, the organ was ideal to accompany choral and congregational singing. Organs originally used hand or foot operated bellows to supply air pressure to the pipes. Electricity was first used in pipe organs in early 19th century with the invention of the electromagnet.

The organ concerto (for organ and orchestra) first evolved during the 18th century with works by Antonio Vivaldi and George Frideric Handel. It’s estimated that Handel wrote about sixteen organ concertos, whereas oddly enough, Johann Sebastian Bach, considered one of the great organists of his time, didn’t write any. Bach was once heard to say, “There’s nothing to playing the organ: you only have to hit the right notes at the right time and the instrument plays itself.” He was of course being unduly modest, but at least reveals he had a dry sense of humour. During the late 18th century, the organ concerto became popular throughout Europe but eventually fell out of fashion. Only a handful of organ concertos appeared during the 20th century the best-known perhaps being that by Francis Poulenc. The organ has also been used as an orchestral instrument in several notable 20th century works.

And that’s another thing. Over the years, I’ve found that church organists sometimes have slightly peculiar personalities. Some are eccentric, even faintly dotty. Perhaps after spending countless hours practising alone in a musty organ loft in the company of a few rats, subtle psychological changes occur. George Frideric Handel had some unusual habits, such as socializing with castrati, not being much concerned about his personal cleanliness and evidently urinating in pots in his bedroom. Handel’s corpulent form, large stature and peculiar lumbering gait earned him the uncomplimentary nickname, “The Great Bear.”

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759): Organ Concerto in B flat major Op. 4 No. 6. Iveta Apkalna (org), Strings of Frankfurt Radio Symphony. Duration: 13:24; Video: 1080p HD

Handel was born in Germany but spent much of his life in England. He made his home in London in 1712, became a British citizen in 1727 and lived at 25 Brook Street in London’s up-market Mayfair district. His Opus 4 consists of six concertos for organ and chamber orchestra written in London between 1735 and 1736. They were originally intended as instrumental interludes in oratorio performances at the newly opened Theatre Royal in Covent Garden. The concertos were played by Handel himself, who already had an international reputation for his technical brilliance and for his innate musicianship. The influential German composer and music critic Johann Mattheson was much impressed. In 1739, he wrote, “One may say that Handel…is not easily surpassed by anyone in organ playing, unless it be by Bach in Leipzig.”

The charming concerto was first performed in February 1736 in the form of a harp concerto, written for the Welsh harpist William Powell. It was intended for performance as an interlude in Handel’s oratorio Alexander’s Feast. Handel later arranged the three-movement work for organ. The music is light and airy and the first movement sounds almost classical in style. In this performance, the movement is lightened by a pizzicato double bass. The last movement (10:01) shows Handel at his most exuberant with graceful melodies, rhythmic drive and a sense of relentless energy.

And just in case you’re wondering, the theatre organ, sometimes known as a cinema organ in Britain, is a rather different animal. In its earliest form, it was virtually a modified piano with a few added sound pipes and various percussive sound effects. It was intended as a cheaper alternative to the “live” instrumental groups that accompanied silent films. The theatre organ uses electricity not only for air pressure but to control keys, stops and air blowers. The air supply to the pipes can be made to pulsate, to create the characteristic vibrato effect. The theatre organ was invented by the organist Robert Hope-Jones whose designs were later taken up by the Wurlitzer Company, a name that has become synonymous with theatre organs.

And just in case you’re wondering, the theatre organ, sometimes known as a cinema organ in Britain, is a rather different animal. In its earliest form, it was virtually a modified piano with a few added sound pipes and various percussive sound effects. It was intended as a cheaper alternative to the “live” instrumental groups that accompanied silent films. The theatre organ uses electricity not only for air pressure but to control keys, stops and air blowers. The air supply to the pipes can be made to pulsate, to create the characteristic vibrato effect. The theatre organ was invented by the organist Robert Hope-Jones whose designs were later taken up by the Wurlitzer Company, a name that has become synonymous with theatre organs.

These instruments contain many ranks of pipes to imitate the sounds of orchestral instruments and all the sounds are controlled from the main console, which unlike church organs, is arranged in a horseshoe-shape for ease of use. Older Brits might recall the name of Reginald Dixon, a brilliant exponent of the theatre organ and closely associated with the Tower Ballroom, Blackpool, where he played for forty years.

There’s an ironic footnote to this. Early in my teaching career, I was accepted as the Head of Music at a large London secondary school. It was unusual in that it had its own chapel complete with an organ. It was a Jennings Model A three-manual organ with pedal board dating from 1959, and it had been installed at considerable expense. “You play the organ, I suppose,” the headmaster had asked me at the interview. “Of course,” I had replied with nonchalant confidence, hoping that the subject would not be pursued any further.

I was expected to play every morning for the school assemblies; two hymns and at the request of the headmaster, a suitable classical piece as the students were solemnly trooping into the chapel. “Ein Stück Kuchen”, as Bach might have said, though probably didn’t. However, I didn’t play many classical pieces, but instead usually entertained the students with improvisations on current pop hits in the style of Bach, much to the merriment of those who twigged what was going on.