If you recognise that expression, you must be getting on a bit. The lines were made famous by an American singer called Chubby Checker and the song entitled The Twist was one of the top songs of 1960. Despite its fatuous lyrics of astonishing vapidity, it was a massive hit. You might recall that the twist was an exuberant dance in the rock and roll days of the early sixties. Thanks largely to Chubby Checker (whose real name was the rather more mundane Ernest Evans) it became a worldwide dance-craze. However, the dance caused concern among the more old-fashioned members of society for being too provocative, just as the waltz had done a hundred years earlier and the dance known as the volta had done in the seventeenth century.

The twist has long since disappeared of course, but the name came to mind the other day when I was removing the cork from a wine bottle. It was a French wine from the Languedoc, and I was mildly irritated to see an ordinary table wine sealed with a cork rather than a twistable screw-cap. Not only that, the cork was reluctant to be parted from its bottle and required by toughest cork-puller I could find in the kitchen and a great deal of physical effort. French wine-makers tend to hang on to tradition but it seemed rather pointless using relatively expensive cork for such a cheap wine. And corks have their problems.

For those comparatively few wines that need twenty or thirty years of ageing to be at their best, that’s a different matter. Cork, with a centuries-old tradition is usually considered ideal for that purpose. For generations, it’s been assumed that that the slow intake of oxygen through a cork plays a vital role in ageing a wine. But more recently, some wine experts have argued that if the cork is perfect, the incoming oxygen is virtually zero. Others argue that any oxygen is detrimental to the wine. No one really seems to agree.

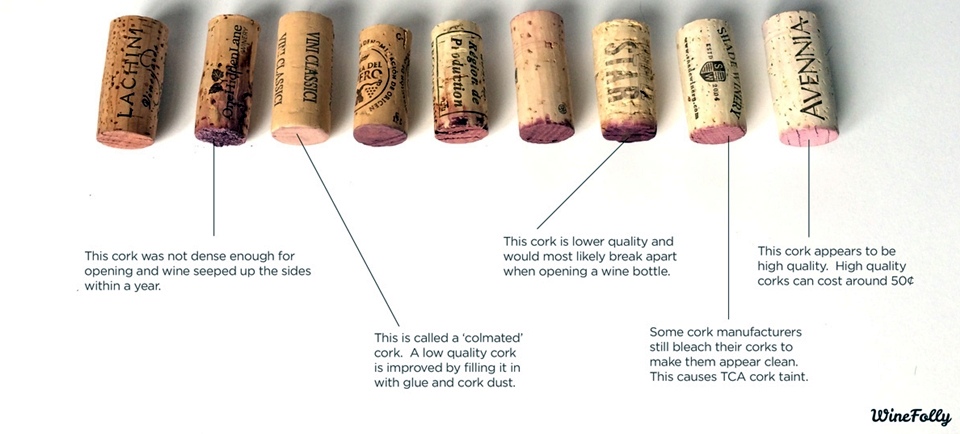

The problem is that cork can be unreliable. It’s been estimated that 2% of all bottles of wine are damaged by cork taint. Wine becomes “corked” when the cork is infected with a fungus that produces a chemical known by the poetic name of 2, 4, 6-trichloroanisole. This makes the wine smell dank, like a wet dog. And if you’re not quite sure what a wet dog smells like, you’re welcome to borrow one of mine after it’s been out in the rain. There would, of course, be a modest fee.

Faulty bottles are more likely to be oxidized rather than corked. Oxidization turns white wines brownish and red wines take on an orange tinge and smell of jammy cooked fruit. It usually happens because of bad storage or transit. When cases of wine are left lying around in a hot loading bay, or spend hours sweltering in the back of a truck, the wine expands in the bottles and sometimes pushes the corks out a little way. When the wine cools, air is sucked into the bottle and oxidization occurs.

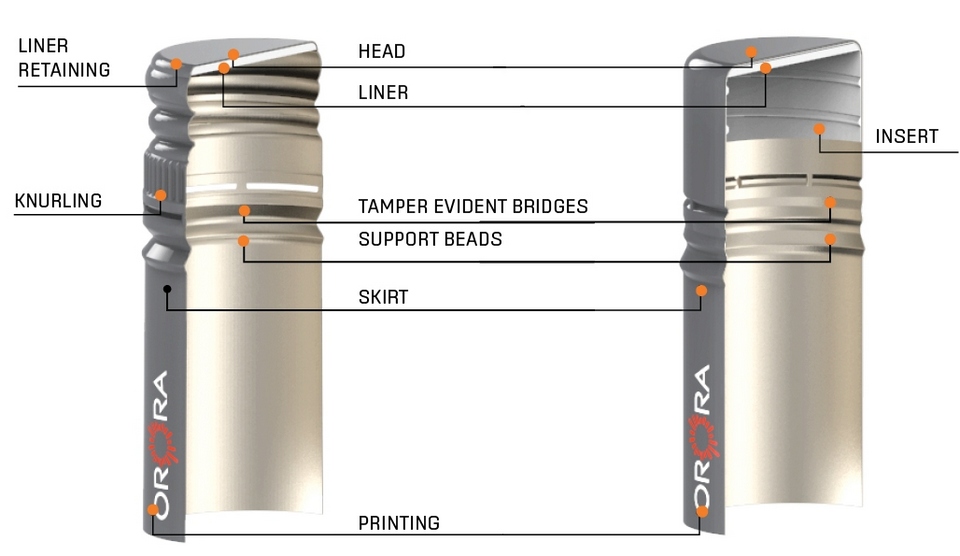

The twistable screw cap is so much easier: an aluminium cap that fits on the neck of the bottle and usually has a metal skirt to resemble the traditional foil. Inside, a layer of plastic, rubber, or other material creates an air-tight seal with the top of the bottle. It’s much better than cork at keeping the air out.

Screw caps have a much lower failure rate, because they prevent oxidation and give the wine a better chance of reaching you in good condition. They’re easier to open too. If I were a wine waiter, I’d much prefer to twist screw-caps all evening rather than go through the tortuous Ballet of the Corkscrew with every customer.

Incidentally, the first wine bottle to feature a screw cap, technically known as a Stelvin Closure appeared in 1959. It was invented by a French company called Le Bouchage Mécanique at the request of the Yalumba winery in Australia. The concept gained acceptance in the wine trade and by the middle of the 1970s, most major Australian and New Zealand wineries had adopted screw caps. As you can imagine, there was some initial resistance because many consumers wrongly believed that they were synonymous with low quality. Today they have become the new norm for wines not intended for long-term storage.

A few days ago, I bought a couple of Australian wines produced by Deakin Estate. This winery lies in the so-called Big Rivers region of Australia, a grape-growing zone in New South Wales. On the map, it’s down near the right-hand corner of the country. Deakin Estate is a relative newcomer to the Australian wine scene. Although the land was bought in 1967, the company didn’t start producing wine until the 1990s, by which time some of the vines had achieved a venerable age.

Deakin Estate Merlot, (red) Australia Bt 650 @ Wine Connection.

This wine is a subdued maroon-red and when you swirl the wine around in the glass, you’ll notice those characteristic “legs” appearing on the inner surface. Contrary to popular belief, these are not an indication of quality but are produced by alcohol evaporation. They’re more pronounced in high alcohol wines, warm weather and high humidity. The technical term is the Marangoni Effect named after the Italian physicist Carlo Marangoni, who in 1865, studied it for his doctoral dissertation. It is not known how many glasses of wine were consumed during his research. In France, these legs are known as “tears of wine” (Larmes de vin) while the Germans refer to them as “church windows” (Kirchenfenster).

The aroma is a typical warm-climate Merlot: plenty of rich cherry on the nose with secondary reminders of herbs, mint and sweet dark fruit. The wine is remarkably smooth; dry of course, but plenty of plummy fruit and a pleasing dash of acidity which helps to brighten the taste. Warm-climate Merlot can sometimes be rather heavy, but even at 13.5% ABV this one is pleasantly medium-bodied. As a bonus, the wine has an attractive long and dry finish.

The people at Deakin Estate have come up with a classy little number for the price: an easy drinker with something interesting to say. It would make a fine partner for substantial foods such as roasts, grills or pasta in a hearty sauce. It would even enhance a lowly beefburger, especially one with a rich mushroom sauce. Frank Newman & Aidan Menzies are the chief winemakers at Deakin Estate. Frank joined in 2014 after decades of winemaking experience. Aidan Menzies, who joined in 2016 is an archaeologist turned winemaker and graduated with honours from England’s University of Brighton

Deakin Estate Moscato (white), Australia. Bt 650 @ Wine Connection

Although sweet wines are usually served only at the end of formal dinners, they can bring an extra dimension to your desserts at home. To wine enthusiasts, the mention of dessert wine invariably brings memories of German Eiswein or Hungarian Tokay. Then there are those two splendid French dessert wines, Sauternes and the rather lesser-known Barsac, both from the Bordeaux region. Because of the high sugar content, they age well and have a lovely soft, slightly syrupy texture though they’re never cloying. The classic wine of Sauternes is Château d’Yquem which is made from a blend of Sémillon and Sauvignon Blanc and regarded with reverence among wine connoisseurs.

You can buy a decent bottle of ordinary Sauternes for around Bt 1,500 but they are difficult to find in these parts. If you’re looking for something less expensive to jazz up your desserts, Moscato can come to the rescue. It’s cheaper and easily available. Surprisingly perhaps, there are over two hundred different sub-varieties of the Moscato (or Muscat) grape and they’ve been around for centuries. Although dry versions exist, the majority of Moscato wines are enjoyed for their sweet, fruity flavors and low alcohol content. In recent years the grape has been grown successfully in Australia.

I first tasted Deakin Estate Moscato about six years ago and was impressed with the quality for such a low price. It’s an easy drinker and would be more accurately described as “semi-sweet. The wine has won several prestigious awards including a bronze medal at the UK’s International Wine Challenge. It’s a pale-yellow wine with faint hint of lime on the aroma and the distinctive smell of sweet raisins. And this incidentally is one of the hallmarks of Moscato, because as far as I know, Moscato is the only wine that smells of grapes. The taste has a delicate acidity and a slightly spritzy quality with hints of green apple which makes it delightful refreshing. At only 6% ABV this wine is typically low in alcohol and it’s perfect as a dessert wine, especially if you’ve been drinking heavier wines with the main course. There’s an attractively long finish too.

The wine proved a perfect match for my home-made apple pie. I use a recipe devised by my Scottish grandmother, who claimed – as Scottish grandmothers evidently do – that she was related to Robert Burns. Perhaps she was, and maybe apple pie was a favourite of old Rabbie, as he was known to his friends. It would be pleasing to imagine that he washed it down with a few glasses of Hungarian Tokay, one of the classic dessert wines. But of course, in those days, he would have had to pull a cork and not “do the twist” with an aluminium screw cap.