A few months ago, an acquaintance of mine decided that he wanted to buy a new mobile phone. He evidently went to one of the large local phone shops and demanded to see “the best and most expensive phone in the shop”. Perhaps this was in the hope that the shop assistants would gasp in breathless awe, though I don’t suppose for a moment that they were much impressed. They probably had a discreet giggle at his ignorance, knowing perfectly well that the most expensive phones are not necessarily the best phones. But it was an interesting lesson, because it reminded me, in a roundabout sort of way, that the expression “the best” is largely meaningless and the connection between monetary cost and practical value is somewhat tenuous. I’ve found that some people hold the naïve view that “the best” is simply their personal favourite. But that’s not much use to anyone else.

You may have come across posts on the social media that list “the best food in the world”, “the best beaches in the world” and other similar claims. I often wonder how these lists are derived and ranked, because the all-important criteria are never revealed. Maybe these lists are simply a summary of public opinion or possibly not even that. I have also seen postings on Facebook (yes, sad, I know) that attempt to rank the “best singers in the world”, or the “best painters in the world”. These nonsensical lists are pointless, though perhaps there is some subtle link with advertising.

However, perhaps I should add that ranked lists of universities or professional reviews of products are a different matter. The Times Higher Education World Education Rankings springs to mind as does the QS World University Rankings. These are serious, well-funded on-going research projects that rank world universities using rigorous professional standards with transparent and clearly-defined criteria. They are intended to help students to identify not “the best” but the most appropriate universities to meet their academic, cultural and social needs.

Kevin Zraly is a distinguished and well-known wine writer and educator, and over the years he has conducted countless wine courses with thousands of students. In his splendid and best-selling text book Windows on the World Complete Wine Course he says that one of the most common questions he is asked by his students is, “What is the best wine in the world?” His answer is always the same: “Red!”

This is an excellent response to a question which has no rational answer, in the same way that asking the name of “the best singer in the world” has no rational answer. Some time ago, I was asked by a friend, a self-confessed wine novice, whether I thought expensive wines tasted better than cheaper ones. Now to my mind, that’s an excellent question. The American author, food and wine critic Robin Goldstein must have thought so too, because some years ago with a group of expert colleagues, he conducted an extensive study on this very question. The researchers eventually produced a paper entitled Do More Expensive Wines Taste Better? which was first published in The Journal of Wine Economics in 2008.

It was a fascinating study as well as a gargantuan undertaking. It was based on a sample of six thousand tastings with over five hundred volunteers aged between 21 and 88 years of age. The volunteers included people who were wine novices, others were wine enthusiasts and some had received wine training. It was an unusual tasting too. While conventional wine tastings evaluate wines using specific defined criteria, this one focused instead on perceived personal appreciation. In other words, the researchers were interested in simply whether the tasters liked the wines or whether they didn’t. Over the course of the experiment, the volunteers tasted five hundred different wines ranging in price from ultra-budget wines costing around $1.65 to top-end products costing around $150. The samples included red, white, rosé and sparkling wines. None of the participants were aware of the price of each wine. Each sample was presented in a “double-blind” style, meaning that neither the server nor the taster knew what was in each glass. This was done so that the servers could not reveal any clues, unconscious or otherwise, about the value of each wine.

The five hundred tasters were asked, “Overall, how do you find the wine?” The only available responses they could use were “bad”, “okay”, “good” and “great”. That might seem somewhat over-simplified, but that’s all the information the researchers required. After the results were analyzed, they indicated that most of the tasters agreed that $20 wines generally tasted better than $10 wines. But as the price (and the quality) of the wines increased, something strange happened. The researchers found that (a) expensive wines are enjoyed more by wine enthusiasts and that (b) expensive wines are enjoyed slightly less by non-enthusiasts. They concluded that non-expert wine consumers should not anticipate greater enjoyment of the intrinsic qualities of a wine, simply because it is expensive or is recommended by experts. In other words, unless you are knowledgeable about wine, you won’t necessarily derive greater pleasure from buying an expensive bottle.

But why should this be the case? Well, I have to admit that I didn’t read the entire research paper because it doesn’t come free and at the time, my month’s reading allowance was used up. However, we know that cheap, commercial wines are intended as crowd-pleasers and they need to appeal to basic tastes. Cheap wines use lower-quality grapes which cannot produce the required depth of taste and richness on their own. To compensate, the wine makers bump up the sweetness levels to make the wine more appealing to the masses.

As Robin Goldstein, the author of the study points out, “What many people don’t know… is that most of us quantify quality as a sense of richness or body in wine. Since richness in wine can be achieved with sweetness (which you can’t easily taste), this could be why cheap wines performed equally, if not slightly better, than expensive wines in the study.”

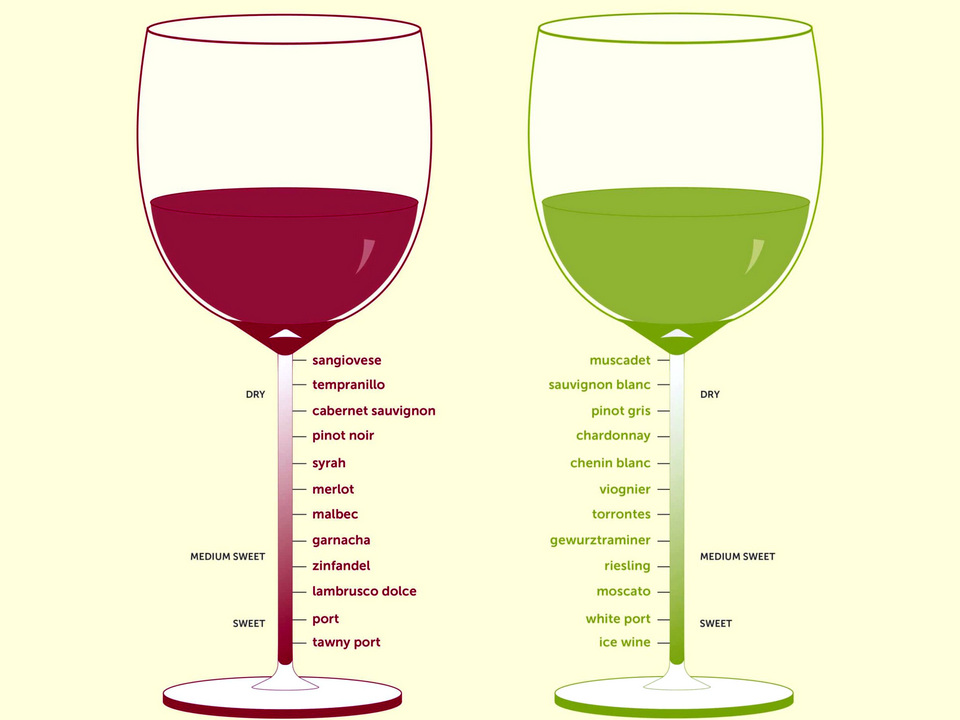

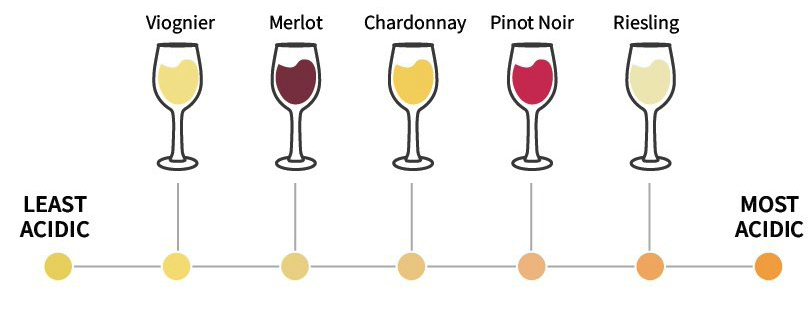

But there are other issues. For example, some quite expensive wines can be a challenge – even to experienced tasters. Acidity for example, occurs more in white wines than reds. Contrary to popular belief, not all Riesling is medium sweet. Some of them are bone dry. I have encountered some expensive ultra-dry Rieslings from the Mösel Valley that have a biting, razor-like acidity which take a bit of getting used to.

Some of the finest Sauvignon Blanc wines from New Zealand can have a toe-curling sharpness that can set your teeth on edge. Then there are tannins, which are found in red wine and can sometimes be a bit off-putting for beginners. Tannins are naturally occurring polyphenols and they occur in berries, beans and chocolate. The tannins in wine come from the grape skins, stems, seeds and barrels and they can have a dramatic effect on a red wine’s mouthfeel and texture. Large amounts of tannins create a puckering astringency on the palate and bitterness that can sometimes prove daunting for the most adventurous of wine enthusiasts.

Tannins occur in all red wines but especially in Cabernet Sauvignon, Nebbiolo, Sangiovese, Montepulciano and the big and bold Malbecs from Argentina. They dominate the appropriately-named Southern French wine grape Tannat, which is invariably blended with other varieties to make it drinkable. Wines that are intended for long-term ageing (such as high-end Bordeaux) are rich in tannins when they are young because the tannins preserve the wine and hold the structure together. As the wines age, the tannins tend to soften.

Another issue is that high-end wines are more effectively appreciated by people with developed tasting skills and who are used to detecting a range of primary, secondary and tertiary aromas, subtle textures and different levels of flavour. It takes experience to learn how to enjoy wine at this level. But that is not to say wine beginners will not enjoy them. They might miss out on the more subtle aspects of the taste and texture but still find it an intensely pleasurable experience. I suppose much the same could be said for various foods such as Beluga caviar, white truffles from Italy, matsutake mushrooms from Japan or moose-milk cheese from Sweden.

I have heard of some people who eat and drink much the same things as they did when they were teenagers. Given the right opportunities, the appreciation of subtle aromas and tastes should become more evolved as we get older and as we gain more tasting experiences. If you get the chance to taste wine which is more expensive than your usual choice, go for it! Seize the opportunity and enjoy the satisfaction and the heady delight of the moment. You never know what pleasures it could bring. You might even find that you have undiscovered talents as a wine taster. Carpe diem, as the ancient Romans used to say.