John Mayall Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton (Decca)

Long ago and far away when I was 14, there was a tiny elite at my age who worshipped “the blues”. They bought Paul Butterfield’s “East-West” when the rest of us bought “Revolver”, they always carried a stack of John Mayall-LPs around and exchanged confidential information. Their hair was longer, and quite often they had access to electric guitars. I felt pangs of envy, and also a disturbing curiosity. What was it they knew that I didn’t?

I never managed to familiarize myself with the coolest of these albums, and quite often I would quip that I preferred “East West” by Herman’s Hermits over the Butterfield-recording (knowing perfectly well that they were two completely different tunes bearing the same title). The quip always sparked dismay. It was a joke of course.

I listened to Mayall a lot. There was stuff going on in there that nailed your attention, even within the narrow blues frame (well, I thought it was narrow) these guys could fly. Not a very ground-breaking observation as the musicians involved were among others Eric Clapton, Peter Green, John McVie, Mick Fleetwood and Mick Taylor – caught just seconds before they turned into monster stars. But I do admit that I liked the other bands they played in much, much better: Yardbirds, Cream, Blind Faith, Fleetwood Mac, Rolling Stones. I was no purist. John Mayall was.

In hindsight we know his importance to the electric blues and blues-rock of Great Britain. Even more than Alexis Korner, Mayall, with his jazz background, his goatee and his whining voice, was the motor of the underground. He saw greatness in these young and gifted talents and cultivated them with love and enthusiasm. He knew perfectly well that they were just passing through. No hard feelings.

Contrary to the later guys passing through the Bluesbreakers’ revolving doors, Clapton already had a name for himself. He left the Yardbirds in frustration when Graham Gouldman’s “For Your Love” turned them into pop stars in the spring of 1965. He wanted to play the blues. So he jumped ship. It was an immature reaction as Yardbirds never sold out but turned into a bold and exciting rock band after he left.

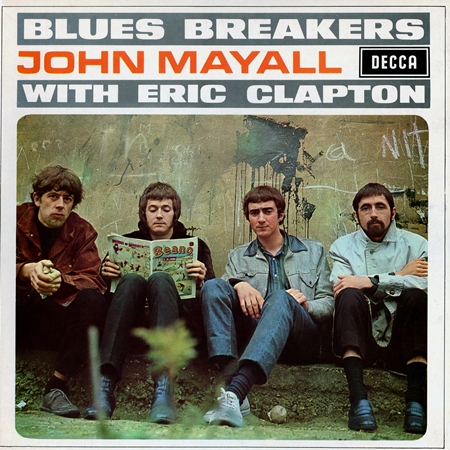

As for Clapton’s purism, he is reading a comic book on the “Blues Breakers”-sleeve, and at the time of the album’s release he had already left for rock music’s first super group, Cream (they would make their live debut a week after the “Blues Breakers”-album’s release).

But the off- and on-engagements with Mayall through 1965 and 1966 was of great importance to him. The blues frame made him relax and Mayall offered him generous space to develop his guitar playing and search for his own sound. After the Yardbirds he’d been a little boy lost. Now he was found.

Mayall offered his soloists a broad canvas to paint on, and Clapton got more than his share. He was the only member of the Bluesbreakers-incarnations that became a serious threat to Mayall himself. People came to hear the guitar god, not old goatee. Decca placed Clapton’s name on the cover knowing that it would sell records. Mayall certainly must have had second thoughts about that, Clapton wasn’t even in the band anymore.

But “Blues Breakers” was a commercial success, Mayall’s first ever, and turned him into a rock star in his own right. During the following years a number of his albums hit the Top 10.

The most sensational thing about “Blues Breakers” is Clapton’s guitar playing. The arrangements are all your typical electric blues with Mayall’s screeching voice and seasick Hammond center stage. But Clapton tears himself loose and delivers blistering solos that represents the dawning of a new era in British rock and also signals the birth of the guitar hero, Clapton being the first of them all.

Although he moves inside the blues there is an individualistic freshness here that bleeds into rock. Clapton’s tour de force is the six minute “Have Your Heard”, where he delivers what many regard as the best guitar solo ever in the history of human kind.

You will find brilliant stuff on Mayall’s post-Clapton albums too – “A Hard Road”, “Bare Wires” and “Blues From Laurel Canyon” to name a few – but none of these caught the zeitgeist like “Blues Breakers” did. That album holds its own and is up there with other 1966 classics like: “Revolver”, “Blonde On Blonde”, “Pet Sounds”, “Aftermath”, “Face To Face” and “Freak Out”, “Fifth Dimension”, “Buffalo Springfield” and… “East-West” (not the Herman’s Hermits recording).

Released July 1966

Side One

“All Your Love” (Otis Rush) – 3:36

“Hideaway” (Freddie King/Sonny Thompson; interpolating “The Walk” by Jimmy McCracklin) – 3:17

“Little Girl” (Mayall) – 2:37

“Another Man” (Mayall) – 1:45

“Double Crossing Time” (Clapton/Mayall) – 3:04

“What’d I Say” (Ray Charles; interpolating “Day Tripper” by John Lennon/Paul McCartney) – 4:29

Side Two

“Key to Love” (Mayall) – 2:09

“Parchman Farm” (Mose Allison) – 2:24

“Have You Heard” (Mayall) – 5:56

“Ramblin’ on My Mind” (Robert Johnson/Traditional) – 3:10

“Steppin’ Out” (L. C. Frazier) – 2:30

“It Ain’t Right” (Little Walter) – 2:42

Personnel

John Mayall – lead vocals, piano, Hammond B3 organ, harmonica

Eric Clapton – guitar, lead vocals on “Ramblin’ on My Mind”

John McVie – bass guitar

Hughie Flint – drums

Additional Musicians

Alan Skidmore – tenor saxophone

John Almond – baritone saxophone

Derek Healey – trumpet

Production

Gus Dudgeon – engineer

Mike Vernon – producer

Recorded

March 1966 at Decca Studios, West Hampstead, London, England

First published in Pattaya Mail on June 27,2013

|

|

|