A fascinating brochure crossed my desk the other day. It was entitled The 15-Minute Retirement Plan1 and gave a concise, easy-to-read guide to retirement planning. I describe the brochure as ‘fascinating’ because it showed both correct and disturbing assumptions and approaches to financial planning.

Time & Money

Making sure we have enough money to live well after you finish work is a complicated task. That’s because we’re dealing with several uncertain variables – or known unknowns as American politics’ original Don, Donald Rumsfeld, might put it.

For a start, we don’t know how long we are going to live. Looking at average life expectancy from national statistics paints a little of the picture but it doesn’t take into account people’s current state of health and their heredity. Most people wouldn’t want to arrange their affairs quite as precisely as heiress Barbara Hutton was alleged to have done (she died aged 66, with no dependents and just $3,500 remaining of a fortune that, in today’s terms, had exceeded $2 billion at the time she’d inherited it).2

As the brochure correctly points out, taking an average is a risky business because we could well live longer (hopefully!) than we expect. Let’s face it, coming out of retirement in your nineties to make ends meet is not an option. So it may be wise to use a national average as a minimum and calculate from there.

As well as calculating a cautious time span for the retirement plan, it’s also important to work out cash flow needs. For example, how much money we would need for everyday life, as well as for big purchases and incidentals. Putting these together gives us a reasonable estimate as to how much money we would need in the pot.

The cost of living

So far this is purely theoretical, however, as we’ve not factored inflation into the equation. The issue with inflation is that we can easily undervalue and – as the brochure’s authors have done – overvalue it. “Since 1925, inflation [in the UK] has averaged 4% a year,”3 we are told. That is true but I find it highly misleading. To begin with, ninety years is far too long a period to use for some retirement planning metrics as, even with increasing longevity, few people alive today are likely to have a retirement that spans such a period. Added to that, the period since 1925 factors in the Great Depression, post-war growth, stagflation in the 1970s, high inflation in the 1990s and the Global Financial Crisis, to name but a few of the events during that period.

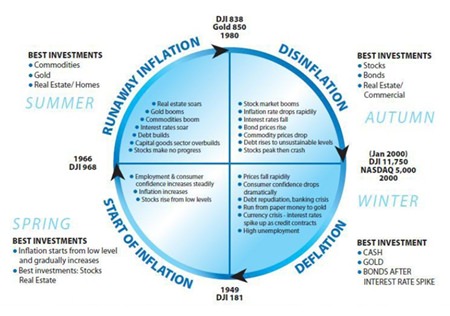

In reality, the economy works in inflationary cycles, as demonstrated by Kondratieff’s Seasons (see graphic).

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2015.

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2015.

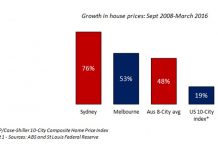

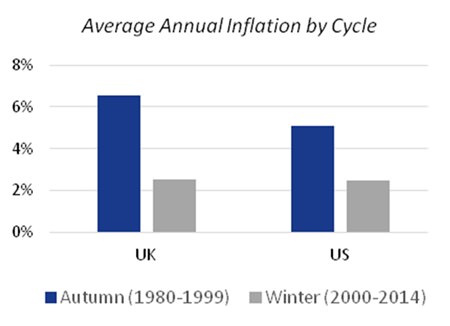

So to say that if we start a retirement fund in 2015, it will need to return an average of over 4% each year until payout is nonsense. For example, if we split the last thirty years into 10-year periods, we can see that the inflationary patterns in the UK and US vary considerably according to the cycle (see chart).

We also need to factor in real interest rates. Financial institutions use central banks’ base lending rates as a benchmark for the rates they charge and pay out. These have been incredibly low for several years: the Fed’s rate has been at 0.25% since March 2009, the Bank of England’s at 0.5% since March 2009, Japan’s at 0.10% since May 2010 and the ECB’s at 0.05% since April 2014.

Typically such low interest rates would encourage banks to offer low rates and therefore people to borrow. Consequently, consumption would increase, driving up inflation, meaning a need for a greater return on investment. However, today we are living in Kondratieff’s winter and a time of great private debt, meaning that whilst real interest rates are not having a fully deflationary effect on prices, it may only be a matter of time before that happens. Zero and negative interest rates are clear symptoms of a deflation, even if it hasn’t yet fed through fully to retail or consumer prices.

Weighing up the options

Along with the above factors, we also have to decide the amount of money we aim to have accumulated at the end of the stated time period. This objective can be broken down into priorities, such as the following: portfolio growth, maintaining its value, depleting assets and targeting a specific end value.

Source: benzinga.com

Source: benzinga.com

Your primary aim could be to increase the purchasing power of your assets as much as possible within the chosen time span. Alternatively, you may merely wish to keep your current purchasing power by the end of the time span. Perhaps you wish to use all of your assets as a means to live in your retirement; or maybe you aim to have a specific end value to pass on to your family.

It’s likely that you would want a bit of each of the above, so this becomes a challenging question of prioritization. For example, if you wish to draw from your portfolio during your retirement, you may have to take aim for higher returns on your investment, which implicitly means higher risk.

The brochure suggested that if the priority was to maintain purchasing power with less volatility, an investor should allocate 70% of his/her investments in equities and 30% in fixed interest investments. However, I feel that this is totally the wrong approach. What we really need is to break it all down by establishing what probability the different levels of risk are likely to bring the return we require.

We can do this using Jensen’s formula designed to find alpha – the measurement of return on investment above the market average. Because this formula takes risk (beta) into consideration, investment managers can work out what kind of return each level of risk can potentially bring, relative to the risk-free rate of interest (which over time has an strong relationship with inflation4).

Using this principle, we should make a decision as to what percentage above inflation we wish our investment to achieve, whilst taking into account the consequences should we not achieve our goal.

An informed decision

That way, we can make an informed decision as to how much risk we are willing to take and what results that risk may bring, based on the realities of modern financial markets; rather than age-old principles or fixed assumptions which may not necessarily be true today.

Footnotes:

1 The 15-Minute Retirement Plan, Fisher Investments UK

2 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbara_Hutton

3 The 15-Minute Retirement Plan, Fisher Investments UK

4 There’s a huge body of academic work on this including large parts of Keynes’ “General Theory” and also Irving Fisher’s “Appreciation and Interest”

| Please Note: While every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is correct, MBMG Group cannot be held responsible for any errors that may occur. The views of the contributors may not necessarily reflect the house view of MBMG Group. Views and opinions expressed herein may change with market conditions and should not be used in isolation. MBMG Group is an advisory firm that assists expatriates and locals within the South East Asia Region with services ranging from Investment Advisory, Personal Advisory, Tax Advisory, Corporate Advisory, Insurance Services, Accounting & Auditing Services, Legal Services, Estate Planning and Property Solutions. For more information: Tel: +66 2665 2536; e-mail: [email protected]; Linkedin: MBMG Group; Twitter: @MBMGIntl; Facebook: /MBMGGroup |