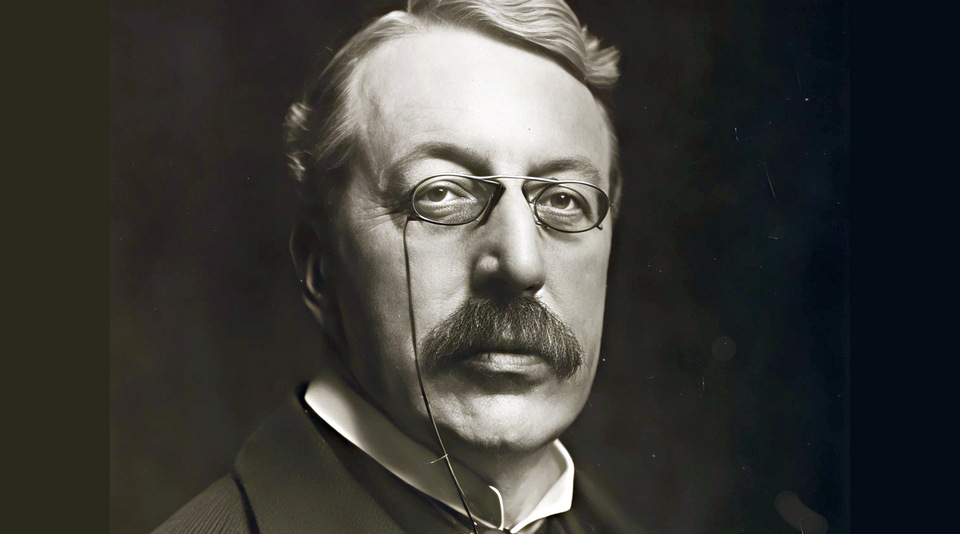

Here’s a question for you. What is the difference between Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and Samuel Taylor Coleridge? Well, of course they are two different people but as a student, I invariably got them mixed up. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (with the hyphen) was born in 1875 and was a successful mixed-race composer of African descent who spent most of his lifetime in London. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, on the other hand was born a hundred years earlier and was a poet, literary critic, philosopher and theologian who had a turbulent career and a personal life plagued by anxiety, depression and illness. His best-known poems are Kubla Khan and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Recently I read the second one again and it’s well-written and quite captivating in its eighteenth-century sort of way. In case you’d forgotten (or possibly never knew), it’s the poem about the seafarer and an unfortunate albatross, and includes the famous but often mis-quoted line, “Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink.”

The two Samuels had such similar names that they must have confused many people. Years ago, I invented the mnemonic “C-T-C-T” standing for “Coleridge Taylor Composed Tunes”. Simple, but it worked. He was the son of Daniel Taylor, a Creole man from Sierra Leone who had studied medicine in London. His mother was the curiously-named Alice Hare Martin and it was she who, in a moment of utter madness or divine inspiration, chose to name her son Samuel Coleridge Taylor (without the hyphen), in honour of the similarly-named poet, thus creating confusion for future generations. Otherwise, the composer would have plain old Samuel Taylor, which admittedly doesn’t have much of a ring to it. Incidentally, in later years, he evidently added the hyphen himself, perhaps to add a touch of gravitas to the name.

Samuel was born in Theobald’s Road in Holborn, in Central London. Seventy years earlier, Benjamin Disraeli had been born in a house on the same street. Samuel’s parents were not married at the time of his birth, and his father had returned to Africa apparently unaware that his wife was pregnant. When Samuel was twelve, his mother Alice married one George Evans, a railway worker in Croydon. In the late 19th century, Croydon was a thriving and rapidly-growing town about ten miles south of Central London and now part of Greater London. The family lived on a street close to the railway line, which must have been convenient for Samuel’s father. Samuel’s maternal grandfather and uncle were professional musicians and it eventually became evident that Samuel also had musical talent. He stared violin lessons and in 1890 at the age of fifteen, he enrolled at London’s Royal College of Music to continue studying violin. Two of his contemporaries were the student composers Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Samuel later changed his main study from violin to composition, and he became a student of the distinguished composer Charles Villiers Stanford.

After Samuel had graduated from college, he was appointed a professor at The Crystal Palace School of Music. The composer Aurther Sullivan was also on the staff. The music school was part of the enormous and imposing Crystal Palace, a building which had originally been constructed in Hyde Park for the Great Exhibition of 1851. It was a massive and magnificent edifice by any standard, covering 990,000 square feet and consisting of an elaborate cast iron frame holding 293,000 panes of glass. After the exhibition, the Palace was dismantled and taken from Hyde Park piece-by-piece to a large open area in South London, though history does not record how many of the glass panes were broken in the process. The re-building was completed in 1854 and the nearby residential area was renamed Crystal Palace in its honour. Crystal Palace Football Club, founded in 1905, had its origins there and still uses an image of the Palace on the club insignia.

The Crystal Palace was never designed for musical performance and with all those panes of glass, the acoustics must have been far from perfect. But it rapidly became the most important concert venue in Britain. For almost fifty years, the orchestral concerts and choral festivals set new standards and introduced new repertoire unparalleled anywhere in its time. The Palace was the venue for the Handel Festival of 1857 which featured an orchestra of 396 musicians and a choir of 1,200. The Crystal Palace Saturday Concerts assisted the renaissance of classical music in Victorian society and some of the leading names in the music world performed there.

Unfortunately, the entire building was destroyed by fire in 1936 but there were evidently no human casualties. The cause of the fire is still unknown and there was never an official inquiry. However, the debts and the unsustainable maintenance costs had allowed the palace to fall into a state of disrepair and the building’s poor condition and large quantities of flammable materials were partly to blame for the fire. Within a mere eight hours, the building was a tangled ruin of iron girders and shattered glass. At the time, it was rumoured that the fire might have been started deliberately. Today, there is barely a trace of this once-great building. The area is now known as Crystal Palace Park and it’s the home of the National Sports Centre with an athletics track, stadium and other sports facilities.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912): African Suite: Danse Nègre. Detroit Symphony Youth Orchestra, cond. Na’Zir McFadden. (Duration: 06:27; Video: 720p)

Coleridge-Taylor must have known Crystal Palace well, for he taught there regularly and undoubtedly attended some of their orchestral concerts. It is likely that some of his own music was performed there. Danse Nègre was the last movement of the composer’s larger African Suite, a series of short pieces composed in Croydon in 1898 when Coleridge-Taylor was already starting to gain a national reputation.

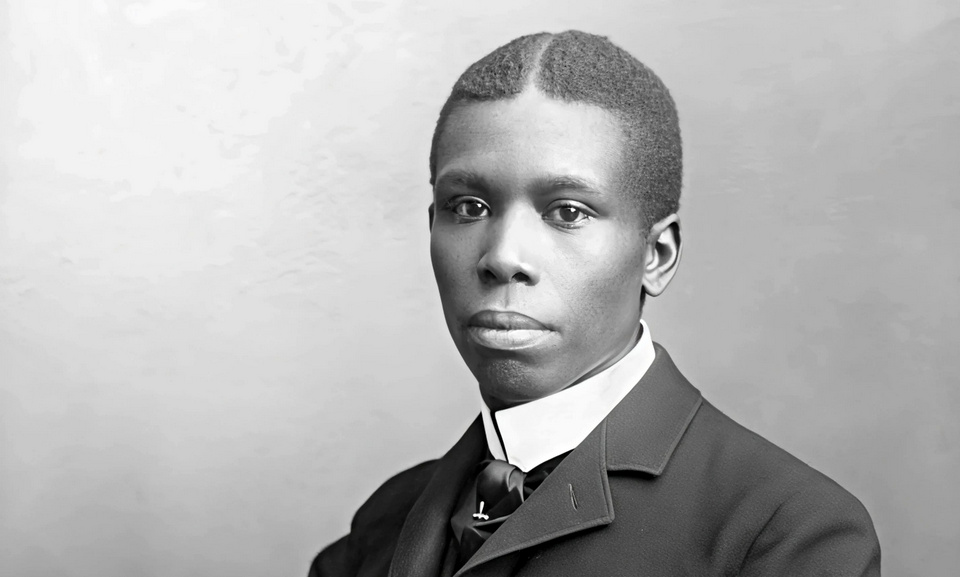

The work was inspired by the writings of the celebrated African-American poet Paul Lawrence Dunbar, whom the composer knew and admired. He was an almost exact contemporary of Coleridge-Taylor and he encouraged the composer to explore his African heritage. Originally written for piano, this is a lively, rhythmic high-energy piece which has become better known than the suite from which it comes. The music shows a compelling command of melodic writing and thematic development. The middle section contains some lovely instrumental writing with some beautiful melodies. If Coleridge-Taylor’s music is new to you, this could be a good place to start.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor: Hiawatha Overture. London Philharmonic Orchestra cond. Joshua Weilerstein (Duration: 12:58; Video: 1080p HD)

Coleridge-Taylor became best known for his three cantatas based on that epic poem of 1855, The Song of Hiawatha by the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The first cantata, entitled Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast was premiered in 1898, when Coleridge-Taylor was twenty-three and the performance was conducted by Charles Villiers Stanford, the composer’s professor at the Royal College of Music. The work proved to be an immediate and long-lasting success, so much so that the publisher Novello commissioned two sequel cantatas which were subsequently named The Death of Minnehaha and Hiawatha’s Departure.

This overture was conceived as an opening number to a performance of Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast at the Norwich Triennial Musical Festival. The premiere took place at the festival’s concluding concert at Norwich Cathedral in October 1899, conducted by Coleridge-Taylor himself. The overture begins magically with a slow introduction accompanied by harp arpeggios. The main theme is loosely based on the spiritual Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen and the music includes lovely melodic writing and brilliant orchestration, a skill that he must have acquired from his teacher Charles Stanford. The composer said that the overture’s intent is “an attempt to reproduce, or, at least, to suggest, the impressions received by the composer on reading Longfellow’s poem.” A critic from Britain’s leading music journal, Musical Times stated, “The Overture is a very fine piece of work…with an…open-air feeling…melodic beauty and vigour of rhythm.”

The fictional character of Hiawatha must have left a profound impression on Coleridge-Taylor. In 1899, he married Jessie Walmisley, who had been a fellow student at college. The couple had a son, who they named guess what? Yes, Hiawatha Bryan Coleridge-Taylor. They had a daughter too, but she was spared the obvious name “Minnehaha” (no doubt to her immense relief) and instead was named Gwendolen Avril Coleridge-Taylor. Both son and daughter had careers in music.

Coleridge-Taylor lived in the Croydon area all his life moving to eleven different houses, but despite his musical successes, he was plagued by financial problems. He made three tours of America in the first decade of the twentieth century and was referred to by musicians in New York City as the “African Mahler.” It’s not clear whether he acquired this sobriquet through genuine admiration, or whether there might have been a touch of facetiousness, for New York City musicians are a hard-bitten lot.

Sadly, Coleridge-Taylor was destined to live a short life and he died of pneumonia at his home in Croydon at the age of thirty-seven. Had medical science been more advanced at the time, he might have recovered, but the fact that he was a heavy and compulsive smoker couldn’t have helped very much. Perhaps, if he had lived another few decades, he might have approached the stature of Gustav Mahler, one of the great names among Austrian composers. Of course, we shall never know.