If you are over A Certain Age you may recall that the original movie entitled Shall We Dance dates from 1937 and was one of the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers musicals. About sixty years later in 1996 an award-winning movie of the same name, but with a different story line appeared in Japan with the Japanese title Sharu wi Dansu (honestly). The title referred in a curiously circular way to a song – also called Shall we Dance from a well-known 1956 Hollywood movie which was banned in Thailand. You probably know the one I mean. Then to confuse the issue even more, in 2004 another American film called Shall We Dance appeared – a remake not of the Astaire-Rogers movie, but of the Japanese one.

Now I’ll be the first to admit that I’m not much good at dancing. Not much good at all. To be more precise I am completely useless. I’d have a better chance of parsing Sanskrit than doing a tango. Strangely enough nobody knows exactly when people started to dance though some archaeologists have traced the activity back to 3,000 BC. Although early dance for ceremonial or religious purposes might have existed without musical accompaniment, it’s difficult to imagine dance without music. For the last couple of millennia music and dance have become inextricably linked.

It wasn’t until the Renaissance that an increasing amount of dance music was written down. Huge collections were produced during the second half of the sixteenth century onwards, notably by prolific composers like Michael Praetorius, Tielman Susato and Pierre Phalèse. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, dance music of all forms flowed from the pens of many composers, including some distinguished ones like Bach, Handel, and Georg Philipp Telemann who wrote suites of dances, not for dancing but as courtly entertainment. In more modern times, composers have often turned to dance music for ideas and inspiration.

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937): La Valse. Philharmonic Orchestra of Radio France cond. Myung-Whun Chung (Duration: 12.55; Video 360p)

This waltz is a fine example of Ravel’s sophisticated use of musical ideas and brilliant orchestration. It’s actually several waltz melodies combined and he called the work a “choreographic poem for orchestra”. Ravel started writing it in 1919 and it was first performed on 12 December 1920 in Paris. It was originally intended to be a ballet but these days it’s usually performed as a stand-alone concert piece.

Although there are unmistakable echoes of the nineteenth century, this powerful work couldn’t be more removed from the innocent waltz melodies of Johann Strauss that were so popular in Vienna and later of course, throughout the western world. Ravel’s waltz sometimes feels more like a surrealist nightmare in a haunted ballroom.

The piece begins quietly with ominous rumbling of double basses and cellos but gradually the tempo and intensity increase, fragments of tune appear and then swirling melodies emerge. You can even get an unsettling sense of foreboding organic growth within the music, as it hurls itself towards an almost terrifying but inevitable conclusion.

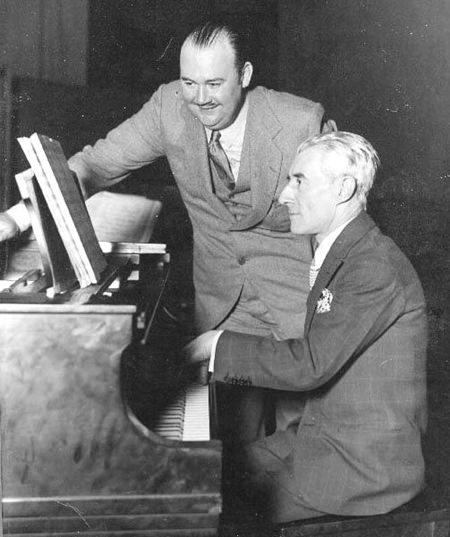

Incidentally, eight years later in 1928 Ravel embarked on a two-month tour of America where he was able to explore his interest in jazz. He met many other musicians and composers there including Paul Whiteman – he of jazz orchestra fame. When Ravel returned to France he started writing his brilliant piano concerto which borrowed many ideas taken from jazz music.

Béla Bartók (1881-1945): Dance Suite. German Symphony Orchestra cond. Ingo Metzmacher (Duration: 16:22; Video: 720p HD)

Hungarian tourist guides enjoy telling visitors that Budapest was once made up of two separate towns. Buda was the old aristocratic town on the hill overlooking the Danube while Pest lay on the flat land on the opposite side of the river. The two towns were officially merged in 1873 and with a flash of original thinking on the part of the city council, the merged city was named Budapest.

In 1923, the council threw an enormous party to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the merger. To bring a sense of gravitas to the event, they staged a grand concert for which the country’s leading composers were commissioned to contribute new works. One of the composers was Béla Bartók, who wrote his Dance Suite for the occasion. Although the composer wasn’t happy with the shoddy performance, the work was later rapturously received during the following years when it was played all over Europe. It probably did more for Bartók’s reputation than all his previous works put together.

Bartók had been studying and recording Hungarian folk music since 1905 and although the melodies in the Dance Suite speak of Eastern Europe they are entirely Bartók’s own invention. The work is full of typical Hungarian rhythms and along with his popular Concerto for Orchestra, it makes an excellent and exciting introduction to the music of this influential twentieth century composer.

|

|

|