A well-established joke among musicians is that harps are like old people; they’re unforgiving and difficult to get in and out of cars. Harps have been the target for musicians’ jokes ever since the instrument appeared in the symphony orchestra during the middle of the nineteenth century. For example, how can you tell when harpists are playing out of tune? Answer: Their fingers are moving.

There’s an element of truth in this, or at least there was twenty years ago before the advent of digital harp tuners. The harp is difficult to tune accurately and unlike the piano which requires a specialist tuner, harpists are expected to do it themselves. The instrument can get out of tune quickly, especially if there are temperature variations at the concert venue. The problem is summed up in another musicians’ joke which asks, “How long does it take to tune a harp?” Answer: Nobody knows yet.

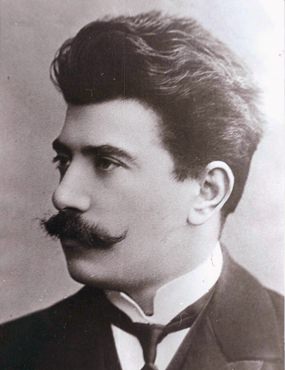

Reinhold Glière.

Reinhold Glière.

Although simple harps were in use as early as 3500 BC the standard harp you see in orchestras today dates from the eighteenth century. It’s technically known as the pedal harp and has forty-seven strings covering a range of six-and-a-half octaves and weighs about eighty pounds. As the name implies, it has seven pedals which are connected to an internal mechanical system that changes the pitch of the strings.

Harps don’t come cheap. You can buy a student model for about $15,000 but a professional instrument could set you back over $100,000. You also need to buy a big van to carry it around.

Surprisingly the harp is popular in Mexico, the Andes, Venezuela and Paraguay and although these instruments have slightly different designs, they have a common ancestor – the Baroque harps brought from Spain during the colonial period.

Reinhold Glière (1875-1956): Concerto for Harp and Orchestra. Elizaveta Bushueva (hp), Moscow City Symphony cond. Sergey Tararin (Duration: 29:45, Video: 1080p HD)

Despite his German first name and his French-sounding second name, Glière was actually Russian. His surname was originally Glier but when he was fifteen, he changed the spelling and pronunciation of his surname to Glière, giving rise to confusion ever since.

The son of an instrument-maker, he was born in Kiev and became an accomplished violinist while still a boy. He took an early interest in composing and during his life wrote four string quartets, eleven operas and ballets, five concertos and three symphonies along with many other instrumental works. His orchestral style, which combined lyricism with traditional harmonies, was much admired by the Soviet authorities who took a dim view of anything that sounded “modern”. Although he was honoured with many awards during his lifetime, today much of his music has fallen into neglect.

This concerto dates from 1938 though you’d never guess. Harmonically and stylistically it’s entrenched in Russian nationalist music of the nineteenth century. But never mind. It’s warm and lyrical with charming melodies and sometimes hints of early Hollywood. If you enjoy the post-Romantic style of Rachmaninoff, you’ll almost certainly take to this approachable work. There’s a delightful slow movement with a delicate melody followed by a lively third movement that culminates in a brief and sunny conclusion.

For a composer, the harp can be a tricky instrument to handle and Glière sought the technical advice of the Russian harpist Ksenia Alexandrovna Erdely. She made so many suggestions that Glière evidently offered to credit her as co-composer, but she graciously declined.

Allan Gilliland (b. 1965): “Gaol’s Rhuah Ròs” A Celtic Concerto for Harp and Orchestra. Patricia Masri-Fletcher (hp), Detroit Symphony Orchestra cond. Leonard Slatkin. (Duration: 11:50, Video: 720p HD)

Allan Gilliland was born in Scotland but moved to Canada in 1972 and settled in Edmonton, Alberta. He’s a prolific writer who’s been described as “one of Canada’s busiest composers” and he holds degrees in performance and composition from the University of Alberta and the University of Edinburgh. He has composed music for solo instruments, orchestra, chorus, brass quintet, wind ensemble, big band, film, television and theatre. This harp concerto was written between 2002 and 2003 when he was Composer in Residence with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra.

The title Gaol’s Ruadh Ròs is Gaelic for “Love’s Red Rose” referring to the well-known song by Robert Burns. This Scottish melody, which we first hear at 05:14 is beautifully harmonized each time it appears and it dominates the concerto. It’s a joyous and approachable work with a brilliantly effervescent opening and you don’t have to wait long for the Scottish influence to appear. The work is intensely rhythmic and makes much use of the Scottish “snap” which is not, as you might imagine, some kind of crispbread from Aberdeen, but a rhythmic device found in much Scottish traditional music and easier to recognise than to describe.