Few composers these days make a living simply by composing music and doing little else. It has nearly always been the case. Composers and other musicians invariably must find other work for a regular income to put bread on the table. One of the most common activities is teaching, either privately or at a music conservatoire. It always has been. In Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries, the church was a major employer of composers, instrumentalists and singers because music has always played a significant role in Christian religious ritual. Almost all baroque and classical composers wrote music for the church, regardless of their religious persuasion.

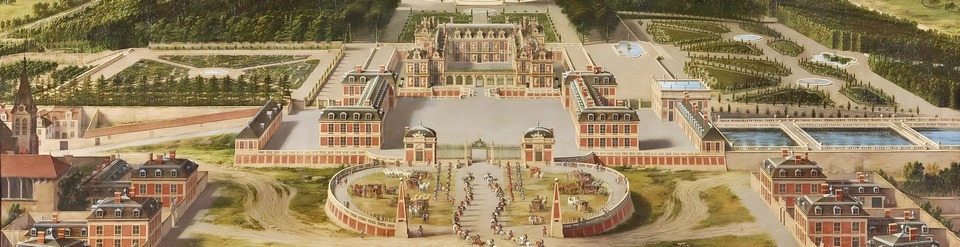

At the same time, Europe was home to a great many royal courts, each serving as a focal point of power, culture and politics. Many courts were also centres for the arts, and influenced music, literature and fashion. The royal courts of France, England Austria and Spain were significant patrons of music. Under Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, music was integral to court life and musicians were employed to entertain and to teach the royal children. In France, at the Court of Versailles, Louis XIV established an enviable musical tradition while in Austria, the House of Habsburg fostered a rich musical environment and was also notably, a patron of Haydn and Mozart.

The courts required a constant stream of new music for concerts, balls, ceremonial and social occasions. Because it was often inconvenient or impossible to obtain printed music, it was easier to commission someone to write music for the occasion, especially when money was no object.

Composers could also supplement their income by writing off-the-cuff informal music for courtly social occasions, or even for private homes if the owners had the financial means to hire a small orchestra or chamber ensemble. This “social music” music was invariably light-hearted in style and scored for whatever instruments happened to be available. Some of the most successful composers in this genre were Mozart, his father Leopold, Carl Stamitz, Joseph Haydn and Luigi Boccherini. There were of course, countless other less well-known composers whose names have faded from history.

Social music usually took the form of a suite of dance-like movements interspersed with slower pieces. It often included many repeated sections to spin out the length. Some of these suites were described as serenades but if that word seemed inappropriate or too romantic, a composer might call the work a cassation, a notturno or sometimes a divertimento. If a little more gravitas was required, the expression Sinfonia concertante could be used. But despite their different names, there was little to distinguish one from another, though the notturno, as the name implies, was intended for performance late in the evening. This “social” music was partly intended to fulfill much the same purpose as today’s background music.

And that’s another thing. For many people today, background music has become a source of irritation rather than a source of pleasure. At one of the best-known supermarkets in Pattaya, there is the continuous tinkling of irritating piano music, the sound of which induces in me a kind of irrational trolley rage. Background music is almost inevitable in restaurants. It is difficult to understand why proprietors of restaurants assume that background music automatically enhances the ambience of a restaurant. Too often, it’s just unwanted noise that distracts from the food, the wine and the conversation. And before you accuse me of being a miserable old git, I should tell you that for the last thirty years, an organization in Britain has continuously and successfully campaigned against obtrusive background music.

It’s called Pipedown, or more correctly the Pipedown Campaign for Freedom from Piped Music and was founded in 1992 by the environmentalist Nigel Rodgers. Piped music, also known as “canned music” or “elevator music” began with the founding of Muzak in the 1930s. It used an audio system invented by an American army general named George Owen Squier. He coined the name Muzak by joining the word “music” with the trade-name “Kodak” which for some reason, he evidently found attractive. In the early days, Muzak didn’t have access to recorded music libraries, so the company hired professional musicians to record original arrangements.

According to opinion polls in Britain, more people dislike background music than like it. Pipedown claims that inescapable background music can have an adverse effect on health, raising the blood pressure and depressing the immune system. And despite all the early hype that background music in supermarkets affects consumer behaviour, Pipedown claims there is no genuine evidence to show that it increases sales. They could well be right, because five of Britain’s major supermarkets thrive without background music. Marks and Spencer switched off background music in all its branches, largely due to of protests from Pipedown members.

Pipedown is supported by many professional musicians and the organisation was famously successful in silencing canned music at London’s Gatwick Airport. In 1994, the airport management surveyed nearly 70,000 people. A significant proportion disliked canned music and to their eternal credit, Gatwick Airport management then switched it off in all the main areas. We really should have a similar outfit to Pipedown here in Thailand, though I suspect it would have a hard time.

Now then, where was I? (I was beginning to wonder – Ed.) Oh yes, by the middle of the nineteenth century, for political and economic reasons, the social order in Europe was changing. Partly as a result, musical performance drifted from the courts to public venues and concert halls, and the serenade and the divertimento temporarily faded from the musical world. During the 20th century, the genre rejoiced in a revival through music by Sergei Prokofiev, Béla Bartók, Benjamin Britten and Leonard Bernstein among several others.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791): Divertimento in D major, K.136. Norwegian Chamber Orchestra, Pekka Kuusisto (artistic director). (Duration: 13:24; Video: 2160p 4K HD)

Mozart composed a large quantity of serenades and divertimenti, some of them intended as Tafelmusik (“dinner music”) for the Archbishop of Salzburg and his ecclesiastical acquaintances. Mozart’s best-known serenade is entitled Eine Kleine Nachtmusik and it took the structural form of a small symphony with four movements. It has become the best-known of all his instrumental works. It was composed in 1787 but no one knows why it was written, for what occasion or for whom. Little is known about the charming Divertimento in D major except that it was written in the winter of 1772, when Mozart was a boy of sixteen and living with his parents in Salzburg. Nobody seems to know the origin of the work except that it was probably intended for a local social occasion. The work has remained popular over the years and its brilliance shows why Mozart’s divertimenti were so admired. For this is not mere background music, but a mature composition of the highest professional quality.

The sparkling opening movement is full of delightful melodies with playful interchanges between the violins. There are sudden moments of lyricism, contrasts of mood and remarkable musical invention. Even the teenage Mozart could be wonderfully expressive, for the slow movement (04:15) seems to exemplify the grace, elegance and expressive depth so valued in the music of the late 18th century. The music is superbly performed by these fine Norwegian musicians, who visibly enjoy playing the work. The bustling high-speed finale (09:20) begins deceptively simply but leads into some animated passages which are brilliantly executed. The technical precision of the musicians is captivating as is their dazzling virtuosity and their use of contrasting dynamics. It is thrilling to hear music that radiates so much passion, excitement and such a wonderful sense of joie de vivre.

Jacques Ibert (1890-1962): Divertissement. NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra, cond. Paavo Järvi (Duration: 17:04; Video: 720p HD)

Despite many difficulties and setbacks, Jacques Ibert had a successful composing career with an enormous output of operas, ballets, incidental music for plays and films, choral works and chamber music. We don’t hear much of his music these days, but this entertaining orchestral suite is probably his best-known work.

The word divertissement originates from the Italian divertire meaning “to amuse” and this suite is a somewhat bizarre take on the divertimento of the 18th century. Ibert based the work on music he wrote for the 1929 production of the classic French comedy play The Italian Straw Hat. The six-movement suite is superbly orchestrated and overflows with vivacity and brash high spirits with several brief quotes from works by other composers. The Introduction has clever “wrong-note” effects with echoes of Stravinsky and Milhaud. The second movement Cortège (01:25) begins mysteriously but transforms itself into a mock-heroic march.

The movement is packed with fleeting musical images, rather like flicking through pages of a photograph album. The short third movement (06.55) is a wistful nocturne showing Ibert at his most poetic. The fourth movement (09:27) is a lively waltz which turns into a surreal and vulgar version of The Blue Danube. The fifth movement (12.38) is a parade which evokes the sounds of a slightly chaotic marching band. After the parade has passed, there’s a wildly incoherent piano cadenza which introduces the Finale, a chaotic circus march in which the players are encouraged by the frenzied blowing of a police whistle. It’s a delightful work which manages to combine catchy melodies, sparkling wit and delicious vulgarity.