“A meal without wine is like a day without sunshine”, wrote Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, the French lawyer, politician and author of the influential book Physiologie du goût (The Physiology of Taste). To many people, especially wine enthusiasts, the thought of wine without alcohol might also seem like a day without sunshine. In a sense, they would be right, because alcohol is one of the most important components of wine. You see, alcohol defines wine and has always been one of its natural ingredients. From the earliest days when wine was first produced in the Caucasus region of Eastern Europe 8,000 years ago, alcohol was there too. Wine was also made in parts of China.

It may be colourless and odorless, but alcohol acts as a preservative by creating an unwelcome environment for certain bacteria and yeasts which, left to their own devices, would damage the wine. Alcohol gives a wine longevity and allows it to age and mature, sometimes for many decades. But more importantly, it’s vital to creating the structure, balance and mouthfeel of a wine. Due to its slightly oily nature, alcohol adds “weight” and viscosity, enhancing the wine’s body and fullness. It also interacts with other compounds, releasing molecules that contribute to a wine’s aromas, flavours and complexity. As any seasoned sommelier can tell you, alcohol – like fats in meat – delivers flavour.

The ancient Greeks and ancient Romans appreciated wine and it was an important part of their culture. In days gone by, it was safer to drink wine than water. Although science has shown that alcohol can be toxic, some studies have claimed that thoughtful and moderate alcohol consumption can decrease the chance of some medical conditions. Everyone is aware that alcohol in excess is dangerous. But so are many other things taken in excess, including medicine, vitamin tablets, food supplements, coffee, salt and doughnuts. Not to mention vehicle exhaust fumes, cigarette smoke and other hazards that many people endure daily.

Wine is basically fermented grape juice. Everyone knows that. Even my dogs know that. As the grapes bask in the sunlit vineyards, they ripen and the sugars in the grapes – primarily fructose and glucose – increase. If left on the vine, wild yeasts in the air would cause natural fermentation that converts the sugars into alcohol. However, the grapes are harvested and taken to the winery before this happens, because wine-makers need to control the fermentation process.

The most common yeast is a species of Saccharomyces cerevisiae commonly known as baker’s yeast or brewer’s yeast. It’s been used for thousands of years in baking and winemaking. It’s used in professional wine making too, along with other yeasts, some of which – like K1V-1116 and RC 212 – sound like names of distant galaxies. Not surprisingly, the more sugar in the grapes, the more alcohol in the fermented juice. But you know, fermentation is not merely a chemical conversion, it’s also a kind of transformative process that turns simple grape juice into a beverage with an astonishing array of aromas, flavours and textures.

Thirty years ago, table wines tended to have between 12-14% ABV (alcohol by volume) and more recently, levels have been creeping upwards, partly because of climate change. The last twenty years have seen a proliferation of high alcohol table wines. Many people don’t particularly care for them and prefer natural low-alcohol wines.

Low alcohol wines typically have an alcohol content of under 11% ABV, making them lighter and easier to drink. They are often made from grapes harvested early, to avoid high sugar levels. They are usually refreshing wines; ideal for al fresco meals, perfect for summer lunches and popular with weight-watchers because lower alcohol carries fewer calories. There are plenty of low alcohol wines at around 11% ABV, especially from Germany and Austria. These provide the advantages of lower alcohol without sacrificing aroma, taste, character and quality. Many of the wines from Germany’s Rhein and Mösel wine regions are naturally low in alcohol, partly due to the lack of sunshine in those northern regions.

But what about zero-alcohol wines? This is an entirely different beverage because the natural alcohol must be removed artificially. Until a few years ago, all European wines had to contain a minimum of 8% ABV, which is why makers of zero-alcohol wines couldn’t describe them as “wine”. Instead, they came up with healthy-sounding brand names.

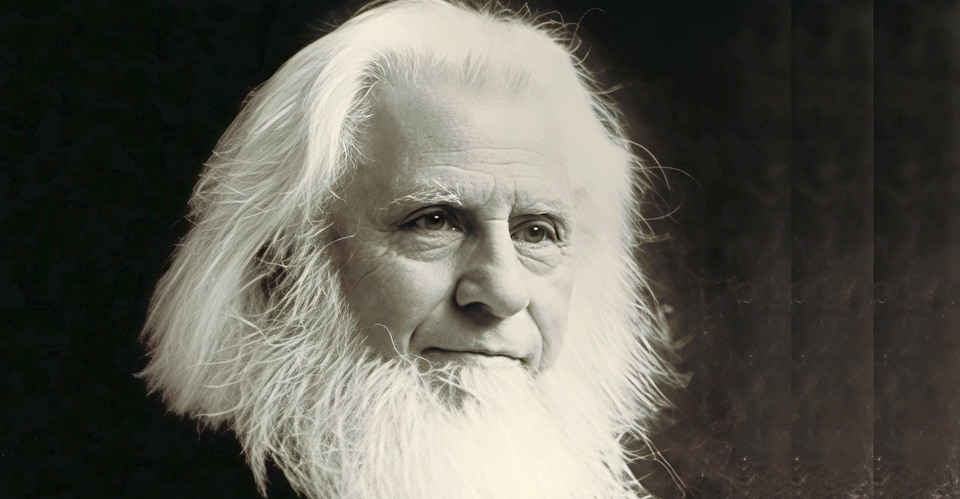

One of those fun-loving Methodists had a phobia about alcohol and was strongly opposed to its use in church. Thomas Bramwell Welch (1825-1903) was a dentist (and a Methodist) from New Jersey who advocated the use of plain grape juice instead of wine. This is richly ironic because wine has been used in the Christian holy communion for over 2,000 years and mentioned in the Bible well over two hundred times.

Unfortunately, Welch’s grape juice had the inconvenient habit of fermenting after a time, thus producing the dreaded alcohol. Welch eventually used a pasteurization process to halt the fermentation. His son, Charles Welch was also a dentist, but when not poking about among oral cavities, ran a company to sell this father’s grape juice to teetotal church-goers. The company is known to this day: it still sells grape juice along with a variety of desserts and snack foods; not the kind of products a dentist would normally recommend.

There have been many other attempts to make zero-alcohol wines, especially in Germany. The problem was that they didn’t taste much good. There are several reasons why people might want zero-alcohol wine, such as convalescing patients, those for whom alcohol is an irritant or those whose religion forbids alcohol. People sometimes turn to low-alcohol or zero-alcohol wines because of the perceived health benefits, real or imagined. There’s been an enormous growth in these products. I first tasted a zero-alcohol wine a good many years ago in London but it was a horrid, thin and watery beverage that smelled of cat food. After that experience, I saw no reason to try zero-alcohol wine again.

Being somewhat cynical, I don’t believe that wineries are making zero-alcohol wine to create a healthier world. For a good many years now, the wine trade has been having a hard time. There’s been a decline in consumption, particularly among younger generations and increased competition from alternative drinks. Inflation and rising costs have added to the problem. Some major wineries are producing zero-alcohol wines because they perceive a highly-profitable niche in the market. Ironically, zero-alcohol wines are usually more expensive than regular wine, because of the additional processes involved.

Zero-alcohol wine starts as regular wine and the major challenge is to remove the alcohol without impairing the other qualities. There are four or five different methods of alcohol removal but the two most common are Vacuum Distillation and Reverse osmosis.

Wine contains about 85% water and Vacuum Distillation uses the principle that alcohol and water evaporate at different temperatures. When the pressure inside the distillation chamber is reduced towards a vacuum, the temperatures also reduce. Alcohol normally evaporates at around 78°C, but in a vacuum, it reduces to around 30-35°C. In this way, the wine can be treated more gently. Reverse osmosis is another common method in which the wine passes through a semi-permeable membrane to filter out the alcohol molecules. De-alcoholization equipment is notoriously expensive, so smaller wineries invariably ship their wines to independent de-alcoholization plants. Wines labelled as “zero alcohol” may contain up to 0.1% ABV. Surprisingly perhaps, ripe bananas, strawberries, blueberries and raspberries also contain up to 0.1% alcohol because some of the sugar has already started to ferment.

Zero-alcohol wine never tastes exactly like regular wine. Removing the alcohol removes the “spirit” of the wine in every sense. The process invariably impacts on the aromas, flavours and mouthfeel. They tend to taste rather “thin” and if you normally prefer rich, full-bodied wine you may well find the zero-alcohol varieties profoundly unsatisfying. I recently sampled a couple of them out of curiosity, partly to find whether they had improved. The samples came from a well-known French company which evidently has an excellent reputation.

The first sample was a bottle of Chardonnay from which the alcohol had been removed by vacuum distillation. Unfortunately, the product must remain nameless. Although it looked inviting, the feeble aroma had a tang of citrus and a mysterious, faintly chemical reminder of something else. I was unable to detect any secondary or tertiary aromas. The most obvious character was the watery thinness and the lack of body and character. Two Thai friends happened to be at the house at the time, so I invited them to sample it. One of them is an occasional wine-drinker though not an expert and the other is virtually teetotal. I gave them the almost-full bottle of Chardonnay and a couple of glasses. A short time later, the glasses were returned with sincere apologies, the wine inside them barely touched. As far as my friends were concerned, the drink was unpleasant, bitter and watery. Mai aroi, as they say in these parts.

The next day, I sampled a zero-alcohol Shiraz from the same company but the less said about it the better, except that it was undrinkable. Even the cat next door turned it down. Sadly, it will have to go down the drain. The wine I mean, not the cat.

I really had high hopes for these two wines. Honestly, I did. But I am afraid that they couldn’t live up to even my generous standards of acceptance. The fact that each bottle cost well over Bt 1,000 added to the disappointment. To me, it simply doesn’t make sense to pay so much for so little. For that money I could have bought a bottle of basic Burgundy or a decent Côtes du Rhône. Even the ubiquitous Thai-produced Mont Clair at a third of the price would have been more enjoyable. If you feel the need to try zero-alcohol wine, proceed with caution. If possible, taste before you buy. For the time being, as far as zero-alcohol wine is concerned, “include me out” as Samuel Goldwyn is supposed to have once remarked.