If you were brought up in Great Britain or Northern Europe, you may have vivid memories of autumn. Perhaps you found autumn captivating, with its intense colours, crisp air and bittersweet nostalgia. Perhaps you found something magical about that time of year, but as a child I found that autumn invariably ushered in a profound sense of gloom. Gone were the long, lazy days of summer; afternoons with nothing much to do except pedal my bike around town, or just lie on the grass in the garden and gaze at the drifting clouds. As September approached, and as the skies began to turn an ominous grey, those carefree memories began to fade. The most exciting event for me was the start of the new school year. But even that was dampened by the autumn chills. Apart from school, autumn always seemed a joyless time of year with the prospect of a forthcoming bleak winter and the fearsome northern gales that swept in relentlessly from the cold, unfriendly Irish Sea.

Of course, there was Christmas on the distant horizon but when you are a young teenager, three months can seem a long time. On our small island off the coast of North Wales, the temperature fell dramatically in September and the biting cold could be almost unbearable. And the rain. The rain! How I loathed the rain back in those days. It wasn’t a warm rain that gently caressed the skin, but a frigid angry torrent that hurled itself out of clouds and drenched everything in its merciless path. It tore the fading leaves off the trees and made pavements slippery with leafy mush. We used to trudge daily to the shambling buildings that formed our school, huddled tightly in thick coats, caps and mackintoshes. Everything was damp. And do you remember that distinctive small of damp coats that pervaded every school cloak room? It was a musty, wet-dog odour that wafted down the school corridors and added to the general air of despondency.

When you come to think about it, “autumn” is rather a curious word. Its origins lie in the ancient Etruscan languages that thrived on the Italian peninsula between about 700 and 100 BC. The word was borrowed by the neighbouring Romans to become the Latin autumnus. It was transformed through old French and into Middle English where it became the odd-looking word autumpne. The popular American word for autumn has its origins in Old English feallan, which means, as you might have guessed, “to fall” or “to fall down”. In sixteenth-century England, people often spoke of “the fall” rather than “the autumn”. Immigrants to the British colonies in North America took their language with them (including “the fall”) but the expression gradually became obsolete in Britain.

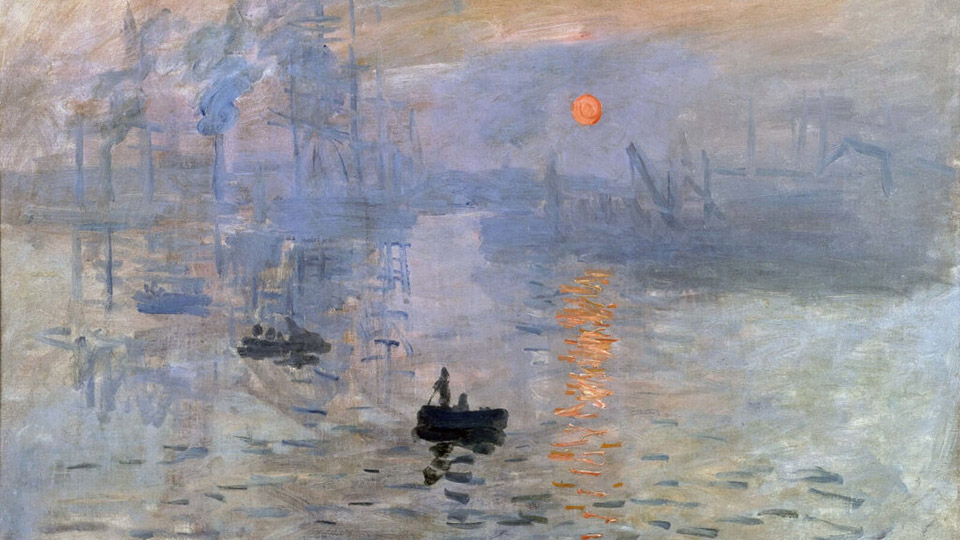

Autumn has proved irresistible to many poets, painters and composers with its associations of melancholia. Our title, The Falling Leaves is taken from a short, expressive poem reflecting on the tragedy and uselessness of war. It was written in 1915 by Margaret Postgate-Cole, an English atheist, feminist, pacifist and socialist and is as relevant today as it was then. The poem has a curious feeling of serene detachment as the writer draws a connection between the falling leaves and soldiers falling in battle, dying “like snowflakes falling on the Flemish clay.” Margaret Postgate-Cole was a classics teacher at St. Paul’s Girls’ School in West London where the Director of Music was composer Gustav Holst, who would later become famous for his suite The Planets. There are many other English poems with an autumn theme. Most British people can quote the first line of John Keats’s poem To Autumn. You’ll probably remember “Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,” even if you’ve forgotten the rest of it. Painters too, and especially the French impressionists were enthused by the colours and atmosphere of autumn.

The popular song, Autumn Leaves is an English-language version of the 1945 French song Les Feuilles mortes and it has become a jazz standard. Ella Fitzgerald sang about Autumn in New York. And you might recall Try to Remember, a lovely, rather melancholy song from the 1960s about a golden, far-distant past and the Septembers of long ago. The English composer Frank Bridge wrote In Autumn, Edward Grieg composed An Autumn Overture and a similar theme was used in works by Debussy, Panufnik and Takemitsu.

Tōru Takemitsu (1930-1996): Autumn for biwa, shakuhachi and orchestra. Akiko Kubota (biwa); Kaoru Kakizakai (shakuhachi), West German Radio Symphony Orchestra cond. Peter Eötvös (Duration 16:31; Video: 1080p HD)

Takemitsu was the most influential Japanese composer of the 20th century. He was an immensely prolific musician too, who composed several hundred works, wrote the scores for more than ninety films and published twenty books on aesthetics and music theory. Surprisingly, Takemistu was largely self-taught. His music often combined elements of Japanese and Western music with subtle instrumental writing and orchestration. Takemitsu once wrote that his work was influenced by Debussy and Messiaen and you can hear faint echoes of their music from time to time during the piece.

The biwa is a four-string Japanese lute which originated in China or the Middle East and first appeared in Japan during the 8th century. It is played with a large triangular plectrum and with its distinctive incisive tone, it was a popular instrument in the Japanese court and in the court orchestra. The shakuhachi is a large end-blown flute made of bamboo and it began to appear in Japanese court orchestras during the 16th century.

Takemitsu was interested in musical textures, organic fragments of sound and orchestral colour, rather than melody and conventional harmony. In this piece, he uses many exotic effects to create a strangely haunting, mysterious and sometimes unsettling sound-world, to which the wailing shakuhachi and the percussive biwa bring their own unique voices. Takemitsu was fond of using periods of silence in his music to create a timeless quality and a sense of emptiness. At the end of the piece, the music slowly fades into total silence.

Takemitsu’s rise to international fame was partly due to a mistake. When Stravinsky visited Japan in the early 1960s, he asked to hear some Japanese orchestral music and the government representatives accidentally put on a recording of Takemitsu’s Requiem, composed in 1957. Stravinsky was so impressed by the work that he insisted on hearing the entire piece and meeting Takemitsu. This seminal moment was the turning point in Takemitsu’s international career though one cannot help wondering what music Stravinsky was supposed to have heard.

Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936): Autumn from “The Seasons”. Youth Philharmonic of Montreal cond. Stéphane Forgues (Duration 07:59; Video: 1080p HD)

Glazunov was a child prodigy who began writing his first works at the age of eleven. He later became an accomplished and prolific composer with nine symphonies, several concerto-style works and many more orchestral pieces to his credit. This ballet was composed in 1899 by which time Glazunov was enjoying international acclaim. The work consists of four scenes or tableau representing each season. It was first performed the following year by the Imperial Ballet in St. Petersburg. The entire Imperial Court showed up for the première, which featured the legendary ballet dancer Anna Pavlova. She, incidentally was one of the few artistes who gave her name to a dessert. Another with this singular honour was the soprano Nellie Melba whose real name was Helen Porter Mitchell. She borrowed the pseudonym “Melba” from her home town of Melbourne. The dessert known as Peach Melba was invented in the 1890s by the distinguished French chef Auguste Escoffier.

The Seasons ballet contains a wealth of captivating music in which Autumn is the fourth and final tableau. The work is in three short movements and begins with the delightful Petit Adagio, full of lovely melodic writing, sumptuous harmonies and richly satisfying orchestration. It’s followed by the rhythmic Variation du Satyre and concludes with the ebullient Bacchanal. Glazunov (like Stravinsky, Prokofiev and Respighi) was a student of the Russian composer Rimsky-Korsakov, who was one of the greatest exponents of orchestration and who ensured that his students mastered this specialist and exacting craft.

Glazunov’s composing and orchestrating skills were never in doubt, but conducting was another matter, and his enthusiasm outweighed his ability. In 1897, Glazunov unwisely conducted the premiere of Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No 1. Although it is now considered one of the finest Russian symphonies, the first performance was an unmitigated disaster. This was partly due to insufficient rehearsal time but, as the composer’s wife later claimed, largely due to the conductor Glazunov being intoxicated. She could well have been right. According to one reliable source, when Glazunov was teaching or lecturing, he secretly kept a bottle of booze hidden behind his desk and enjoyed the occasional slurp with the aid of a long rubber tube. It obviously didn’t remain a secret for very long.