When I was young, our family lived in a house opposite Chitralada Palace, within the Dusit Palace grounds in Bangkok, the royal residence of King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) and the Royal family. On those vast grounds utilized for ceremonies, the King also carried out many projects, including agricultural experiments and innovations for rural development.

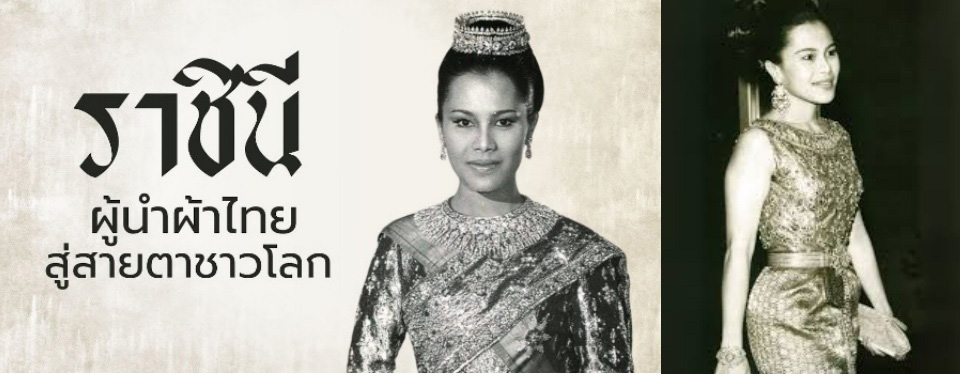

From our house, we saw only the long palace walls and the surrounding moats. The rare times we glimpsed the royals were when their convoy passed by, the King and Queen sitting in their yellow Rolls-Royce and waving to people lining the streets. Mostly, however, we saw them on television: daily palace news in black and white. Some segments showed ceremonies, but many featured their visits to rural provinces, initiating or following up on their projects. My father admired the King’s work; my mother admired the Queen. “She is so well dressed, so poised, so elegant. And so kind,” she would say.

The following story honors this extraordinary Royal couple, yet it centers on the beautiful Queen Sirikit and her remarkable role, vision, and dedication.

Among Her Majesty’s many projects to uplift the poor, the revival of Thai silk was one of the most significant, not only for supporting villagers’ income but also for bringing Thailand’s ancient handicraft heritage to global recognition.

Ancient Threads

The journey of Thai silk goes back almost 3,000 years. In Ban Chiang in northeastern Thailand, archaeological discoveries of silk threads and loom parts show that Thai weaving is among the oldest living textile traditions in Asia.

For centuries, the gentle rhythm of wooden looms echoed through Thai villages. Women sat beneath wooden houses on stilts, weaving silk dyed with natural colors from indigo, tamarind, and tree bark. Each region had its signature patterns: the shimmering Mudmee of Isan, the elegant Yok Dok of the central plains, and the flowing Lai Nam Lai of the North. Yet for a long time, these treasures remained largely unseen.

In the early 1900s, Thailand was still developing, and life in rural areas was difficult. Most villagers survived on small-scale rice farming. Handicrafts were made mainly during the dry season, often for their own use or for small local trade. Few believed their woven cloth had real economic value.

Eye on Silk

In the 1940s and 1950s, an American, Jim Thompson, fell in love with Thai silk. Working with rural artisans, he helped refine colors and patterns and introduced the fabric to global fashion houses and Hollywood productions such as The King and I. Through him, the world saw the beauty of Thai silk, although its fame remained mostly among the wealthy, while the villagers who created it stayed poor.

Then came the person whose vision, intelligence, and compassion would transform the craft and the lives behind it: Queen Sirikit of Thailand.

The Queen and the Villages

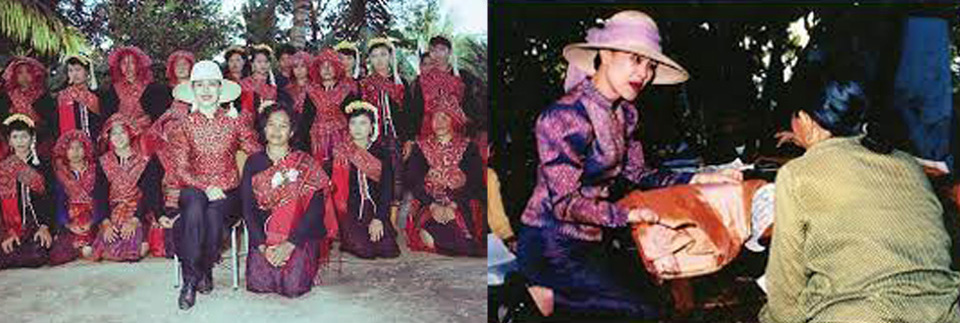

After her marriage to King Bhumibol in 1950, Her Majesty accompanied him on countless visits to remote villages. While the King focused heavily on land development and irrigation, especially in the Northeast, where the land was prone to drought, it often cracked under the sun. The Queen witnessed firsthand how villagers lived. With limited or no education and few opportunities, most depended on small farming and selling handmade crafts.

It was during these visits that she noticed women weaving exquisite silk and cotton pieces in their spare time. Overjoyed by the royal visit, villagers often presented the Queen with their best Mudmee and handwoven textiles crafted painstakingly over many months.

Moved by their skill and hardship, Her Majesty gently encouraged them, planting the seeds of what would become the SUPPORT Foundation under her royal patronage.

She told them: “They are so beautiful. Please start weaving again. I will buy them all.” “If you wove them for the Queen, I would wear them all the time.”

Her praise ignited a revival. Palace staff began training villagers, improving techniques and patterns.

Her team would quietly ask for even the smallest woven scraps and pieces villagers used as household cloths or wiping rags, because to Her Majesty, every thread carried knowledge worth preserving.

Soon after, Queen Sirikit established the SUPPORT Foundation, which provided fair income, training, and new opportunities for artisans nationwide. For the first time, many weavers were paid directly by the royal household.

One elderly weaver recalled:

“Thanpuying Suprapada (private secretary to the Queen) gave us 100 baht per cloth. I had never earned anything from weaving before.”

That may sound cheap in 2025, but in the 1970s, rural daily wages were 15–20 baht a day. Now, rural labor wages are 330–370 baht. Today, a piece of cloth of this quality would be priced at least 3,000 to 5,000 baht. Thus, In those days, 100 baht was a life-changing amount for villagers who normally earned nothing at all from their weaving. It was enough to feed a family for weeks. And the more they wove, the more they earned. They realized their labor had economic value, along with self-worth and honor from the recognition of the Queen herself.

Queen Sirikit often expressed her admiration, saying that Thai people possess artisan’s blood, farmers, laborers, and anyone.

“With training, their skills would emerge.”

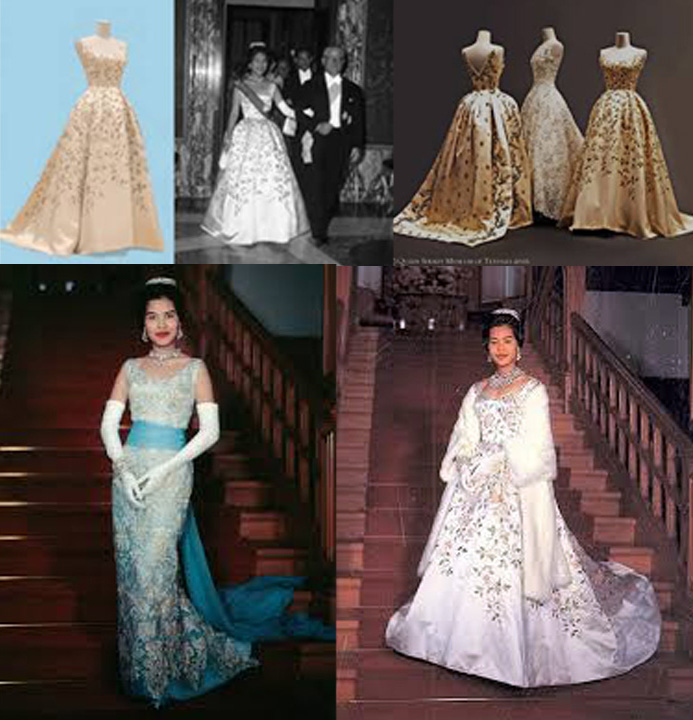

Thai Silk on the World Stage

After acquiring locally woven fabrics, the Queen worked with the palace designers to craft traditional Thai costumes of many styles, modernizing the cuts and patterns suitable for different occasions. From the early 1960s onward, she also commissioned the French couture house Balmain, led by Pierre Balmain and later Erik Mortensen, to create gowns for her state visits to Europe, the United States, and beyond. These masterpieces blended handwoven village silk with Western haute couture, earning praise as a global style icon.

Her choices showcased Thai craftsmanship on the world stage and proved to villagers that their textiles could reach far beyond their communities. Her example restored dignity to women, once seen only as poor farmers.

Lifelong Projects

Her Majesty initiated and supported thousands of projects. Among the most emblematic were Thai silk, rural health, forest and water conservation, Khon dance, wildlife protection, hill-tribe support, education, and herbal medicine. These projects brought training, knowledge, and self-reliance to communities that once lived from harvest to harvest.

Her efforts complemented King Rama IX’s more than 4,000 royal projects, many centered on water and irrigation, providing farmers with year-round water, thus improving their crops and livelihood.

Queen Sirikit famously said:

“If His Majesty the King is water, I will be the forest, the forest that shelters and nurtures the water. The King creates reservoirs, and I will plant forests.”

Legacy

When Queen Sirikit, the Queen Mother, passed away in October 2025, the nation mourned a mother who had uplifted her people with gentle hands. To me, it marked the end of an era that my generation lived through, remembered, and deeply appreciated.

Our dear Queen rests in peace, while her legacy lives on in every loom, every silk thread, and every village that now weaves not just for income, but with pride and purpose.

Today, when Thai silk shimmers in sunlight, or under chandeliers, it carries the memory of Ban Chiang’s ancient threads, the artistry of humble village hands, and the enduring vision of a compassionate woman who turned survival into dignity and tradition into national pride.

Queen Sirikit, Mother of the Nation, will forever live on in the Threads of Time.