Do you have a special place? I don’t mean the bar down the road, but somewhere perhaps from the past which is forever ingrained in your consciousness. Maybe you have childhood memories of your home-town, your grandmother’s house or the corner of the garden in which you used to play as a child. Or possibly it’s some favourite rocks on a well-loved beach or a place you once went on holiday. Your special place might be somewhere that you’ve visited many times. It might be somewhere less specific, like the middle of a cornfield, the top of a hill or somewhere close to a river. You may have cherished memories of sitting under a tree in someone’s garden. It might no longer exist physically except as a vivid memory in your mind. The place might be special because something significant in your life occurred there or it might feel special for no obvious reason.

Most of us have special places in our lives, sometimes locked deep in our memories, to privately treasure during moments of reflection; a place that somehow resonates with our very being. The Aboriginal Australians believe that each person has a specific place in the world where they most belong: a place they experience profound feelings of belonging and somewhere that resonates deeply with our awareness.

The Welsh language has a wonderful word for this feeling. The word is hiraeth and it means a kind of homesickness, sometimes tinged with melancholy sadness over something lost or departed. It’s a longing, yearning, nostalgia, wistfulness or an earnest desire for something from the past. Perhaps you have experienced that same, poignant emotion when you think about your special place, especially if it no longer exists. Strangely enough, the word hiraeth has no exact English translation. In 1948, the English poet W. H. Auden coined the unlovely word topophilia to describe the feeling, but it sounds more like some kind of disease and has none of the emotional and melancholy connotations of “hiraeth”.

The Welsh language has a wonderful word for this feeling. The word is hiraeth and it means a kind of homesickness, sometimes tinged with melancholy sadness over something lost or departed. It’s a longing, yearning, nostalgia, wistfulness or an earnest desire for something from the past. Perhaps you have experienced that same, poignant emotion when you think about your special place, especially if it no longer exists. Strangely enough, the word hiraeth has no exact English translation. In 1948, the English poet W. H. Auden coined the unlovely word topophilia to describe the feeling, but it sounds more like some kind of disease and has none of the emotional and melancholy connotations of “hiraeth”.

In 2017, the British National Trust, in cooperation with the University of Surrey carried out extensive and detailed research to discover more about the “special place” phenomenon. They discovered that most people experience this and 42% of them have special places connected with their childhood years. Using a type of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, the studies found that certain areas of emotional processing in the brain create a powerful response to a place with personal meaning. This response affects us physically and psychologically and indicates that there’s a strong physical and emotional connection between places and people. The research also showed that special places have a positive effect on our sense of well-being. It seems that the Aboriginal Australians are not far off the mark.

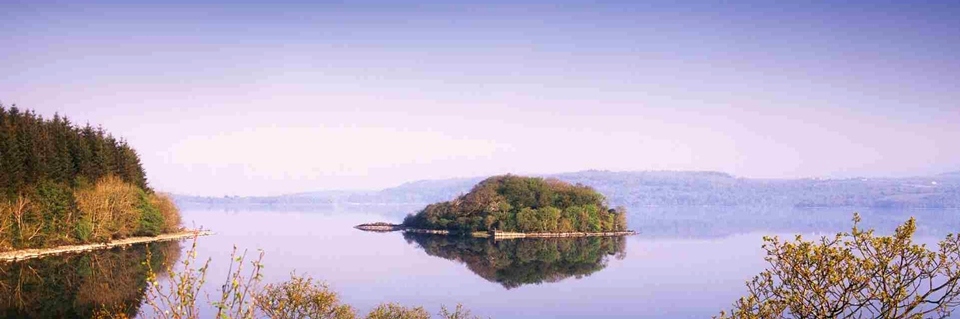

Innisfree is an uninhabited island in an Irish lake where, during the 1870s the poet William Bulter Yeats spent his childhood summers. As a young adult living in London, he had a sudden memory of the island and wrote, “I had still the ambition…of living on the little island of Innisfree”. This must have been the poet’s “special place” and it became the inspiration for a short poem of the same name. During Yeats’s lifetime – evidently to his annoyance – it became one of his most popular poems. Perhaps that was because the notion of a “special place” resonated with so many people.

Poems about places have the power to transport us to cherished locations and let us experience the world through the poet’s words and imagery. You may have encountered some of these poems by Wordsworth, Keats or Tennyson which create this bittersweet emotion. Probably almost every poet has written something on this theme: it is so tempting. And as the Danish and slightly eccentric author Hans Christian Andersen famously observed, “When words fail, music speaks.” He was expressing the idea that at times, human experience or emotion becomes too intense for language alone. Music can carry emotion, mood, tension and release in ways that reach directly into the listener’s consciousness.

I can think of many pieces of music that evoke “a sense of place”. When I was a small child, I loved the popular song The Deadwood Stage which was a hit record for Doris Day in the early fifties. In my innocent mind, it created a vivid picture of the Old West: the sun high in a clear sky and a horse-drawn stage coach clattering along a dusty track in a wild and rocky landscape. Perhaps the stereotypical imagery came from Hollywood but even so, that jaunty song created in my mind the notion of a sense of place.

In some of the moody orchestral music of the Brazilian composer Villa-Lobos, you can almost smell the dense, humid Brazilian forests. Sibelius too had the uncanny ability to create musical images of his bleak Finnish homeland. The music of Vaughan Williams and Frederick Delius invariably evoke images of England’s rural landscapes and rolling hills. Aaron Copland, the American composer often referred to as “the Dean of American Music” had a similar gift.

Aaron Copland (1900-1990): Appalachian Spring, Suite. Philharmonia Orchestra cond. Santtu-Matias Rouvali (Duration: 27:06; Video: 1080p HD)

Copland’s music often evokes the vast spaciousness of the American prairies. Even during the first few moments of Appalachian Spring, you get a distinct sense of place. This work was commissioned by the legendary ballet dancer and choreographer Martha Graham and first performed in 1944. The ballet is set in a village in 19th-century Pennsylvania and it’s full of traditional American themes, including the Shaker song Simple Gifts, which Copland borrowed and wove into the music.

You might recognise this tune as the popular hymn Lord of the Dance. The orchestral suite, using music from the ballet was composed in 1945 and the movements are fine examples of orchestration at its best. Interestingly, when Copland wrote the music, he referred to it as the “ballet for Martha” having had no title in mind. Martha Graham herself suggested the title “Appalachian Spring”, inspired by a poem by the American writer Harold Hart Crane entitled The Bridge. Interestingly, the word “spring” in the poem refers not to the season, but to a stream of water. Not many people know that.

Frederick Delius (1862-1934): In a Summer Garden. Frankfurt Radio Symphony cond. Sir Andrew Davis (Duration: 16:32; Video: 720p HD)

Frederick Delius was an English composer, born into a prosperous family in Bradford. His parents had German roots, hence his rather un-English name. Delius used the forename Fritz until he was about forty. He had his first musical successes around the turn of the century and composed his most popular works in the following couple of decades. The garden in the work’s title refers to Delius’s own garden at his home in Grez-sur-Loing in France where he lived with his wife, Jelka.

The small town is deep in the French countryside, about an hour’s drive south of Paris. The house, large but somewhat nondescript from the outside, must have been a special place for Delius. He made it known that after he died, he wanted to be buried in his own garden but the French authorities wouldn’t have it. His alternative wish – despite his atheism – was to be buried “in some country churchyard in the south of England, where people could place wild flowers”. And so he was, at St Peter’s Church in Limpsfield, Surrey.

The work reflects the composer’s profound passion for nature, a theme that recurs in much of his music. The music mostly has a gentle, pastoral quality and is similar in many ways to his two other works On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring (1912) and Summer Night on the River (1911). His composing technique is fascinating because Delius uses of fragments of melody – simple but elegant phrases really – and builds them into a rich tapestry of colour and movement. The result is a fluid and impermanent quality, something akin to the artistic style of the French impressionist and pointillist painters.

During the work, he uses different colours and textures giving an impression of fleeting impressions rather than a static image. Shifting patterns of sounds appear then dissolve and drift away, suggesting the movement of dappled sunlight on leaves and gentle breezes. Gradually the character of the music changes into a stormier mood of dramatic intensity before slowly and quietly dying down to the quiet state of mind that opened the work. It ends almost inaudibly with the most delicate orchestral sounds. It’s a beautiful evocation of a special place and as a composition it’s a technically a brilliant piece of considerable complexity. But more importantly it creates a wonderful sense of imagery, a kind of dream-like feeling which envelops the listener with its tantalizing magic.