Dancing the night away

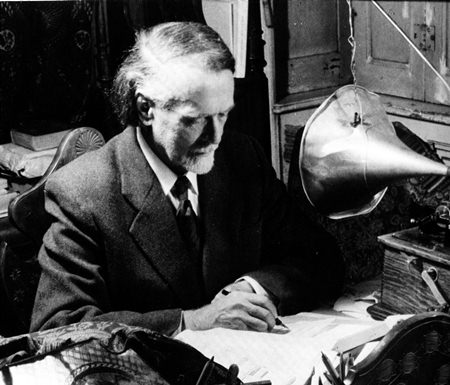

Zoltán Kodály analysing folk-song recordings.

Nobody knows when humans

started dancing, but it must have been a very long time ago. It was probably a

natural expression of joy or elation and I suspect many generations elapsed

before the concept of ritual dancing emerged. But of course, all this is so far

back in human history that we simply don’t know. Your guess it as good as mine

and to be honest, probably better.

We know that formalized

dancing was practised among the ancient Greeks, because various artifacts depict

dancers and musicians. Even so, we don’t know very much about what the music

actually sounded like. It wasn’t until the Renaissance began to dawn, that an

increasing amount of dance music was written down. Huge collections were

produced during the second half of the sixteenth century onwards, notably by

prolific composers like Michael Praetorius, Tielman Susato and publisher Pierre

Phalèse.

Leuven lies about sixteen

miles east of Brussels and Pierre Phalèse started a bookselling business there,

which developed into a successful publishing house. By 1575 he had produced

nearly two hundred music books, many for the lute - a popular instrument for

singing and dance music. At first, Phalèse outsourced his books to various

printers, but later produced his own music books using state-of-the-art

technology, movable type.

During the sixteenth and

seventh centuries, dance music of all forms flowed from the pens of many

composers, including some distinguished ones like Bach, Handel, and Georg

Philipp Telemann who wrote suites of dances, not necessarily for dancing but as

courtly entertainment.

Zoltán

Kodály (1882-1967): Dances of Galánta.

London

Philharmonic Orchestra cond. Vladimir Jurowski (Duration 15:23 Video 720p HD)

Zoltán Kodály (zohl-TAHN

koh-DAH-yee) is best known as the creator of the so-called Kodály Method.

He became interested in children’s music education in 1925 when he happened to

hear some school kids singing in the street. He was horrified by their tuneless

squawking and drew the conclusion that music teaching in the schools was to

blame. He set about a campaign for better teachers, a better curriculum, and

more class-time devoted to music. His tireless work resulted in many

publications which later influenced music education world-wide.

Kodály is most closely

associated with a teaching aid he didn’t actually invent: the hand signs. The

so-called Kodály hand signs were devised in the mid-nineteenth century by an

English minister, John Curwen and they represent each note of the scale. They

were used in the 1977 movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind, but they

didn’t seem to fit the plot and were perhaps merely included to add a bit of

gravitas to a rather implausible scene.

Kodály wrote Dances of

Galánta in 1933 using folk music of the Galánta region, now part of

Slovakia. The work is in five sections and the clarinet is especially

prominent, because it represents the traditional Hungarian tárogató, a

single reed instrument whose conical bore produces a unique sound, somewhere

between that of an oboe and that of a soprano saxophone.

Alberto

Ginastera (1916-1983): Dance Suite from “Estancia”.

Simon Bolivar Orchestra of Venezuela cond. Gustavo Dudamel (Duration: 12:52;

Video: 480p)

Alberto Ginastera (jee-nah-STEHR-ah)

is considered the most powerful voice in Argentine classical music. He studied

at the conservatoire in Buenos Aires, and later with the American composer Aaron

Copland. Ginastera’s music can be challenging, percussive, thrilling,

thought-provoking and sometimes even downright scary.

The thunderous last

movement of the dramatic First Piano Concerto was brought to fame in 1973 when

it was adapted by the rock group Emerson, Lake & Palmer. Ginastera even

approved of the arrangement, which relied heavily on keyboards and synthesized

percussion.

Much of Ginastera’s music

is nationalistic and draws on Argentine folk themes or other elements of

traditional music. He greatly admired the fine Gaucho traditions and this is

reflected in his 1942 one-act ballet Estancia (“The Ranch”). It’s a

story about a city boy who falls for a rancher’s daughter, but the girl finds

him weak and dull compared to the macho and intrepid Gauchos. Ginastera turned

the ballet music into a delightful four-movement orchestral suite and if you

haven’t heard Ginastera before, this is a great place to start. All the

hallmarks of his style are there: his love of percussive sounds, his sparkling

angular melodies and his tremendous sense of rhythm.

You would need a heart of

stone to not be moved by the dazzling last movement (at 09:04) which is an

absolute “must hear”. The closing section (at 10:47) is thrilling, with

cataclysmic percussion and brilliantly articulated playing.

The Simon Bolivar

Orchestra of Venezuela is the direct result of another dedicated music educator,

José Antonio Abreu, who developed a music education programme in Venezuela known

as El Sistema. This young Venezuelan orchestra is superb and the

brilliant, musically-gifted conductor Gustavo Dudamel clearly enjoys every

moment of this action-packed music.