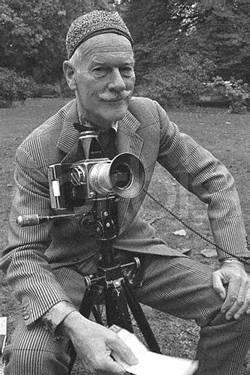

Norman Parkinson has been dead for many years, but the photographic world is that much poorer without him. He was a photographer who could lend his hand to photograph any subject, be that fashion, portraiture, reportage or travel. His version of the Pirelli calendar remains one of the best, with subtle reference to the tyre manufacturer through the use of the tread pattern in each of the 12 nudes. He was a man who gave great thought to how he would take any shot – not just working out the exposure details.

However, I will always remember Norman Parkinson for the famous tale of his apprenticeship and his reaction to the ‘superiors’ of his day. He was indentured to Speaight of Bond Street, the ‘Court’ photographer in 1931 when he was eighteen years old. Those were the days when you paid to be allowed to work under such important people, and Parkinson’s fee which he had to pay was three hundred pounds to able to learn from the ‘great man’.

Norman Parkinson

Norman Parkinson

Speaight had once photographed Kaiser Wilhelm in the trenches and would regale his students with the tale, and how he used a bed sheet to reflect the light into the face of his famous subject. “What do you think the exposure was?” he thundered at Parkinson. “About a fortnight at f8,” was his cheeky reply. That quick-witted response epitomizes Norman Parkinson’s approach to photography as well. Quick to adapt and an underlying sense of humor.

After leaving Speaight, Parkinson set up his own studio in London. He was twenty one and willing to experiment with lighting and was soon in demand from the young debutantes of the day. However, Parkinson soon felt hemmed in by the confines of his studio, but when Harper’s Bazaar magazine commissioned him to photograph hats out of doors, Parkinson was off.

With a hiatus for the war years where he worked in aerial reconnaissance, Parkinson came back with a rush and worked for the international Conde Nast group, with the bulk of his work going into the British and American Vogue magazines. He is credited as having had an enormous influence on post war American fashion photography, setting the trend in that country also in using the outdoors as the backdrop.

His favorite way of shooting outdoors was “contre jour” (against the light) and to use a fill-in flash to light the foreground. Parkinson did this because when you take a shot with the sun behind you, there is no way you can control or modify the light source, but by using fill-in flash he would retain total control, balancing the foreground illumination against the light from behind the model, as supplied by the great celestial lighting technician. This style of photography I have mentioned many times in these columns and is worthwhile experimenting with.

Like all true professionals, Parkinson carried more than one camera on a shoot and would have two sets of medium format cameras (Hasselblads) and another two sets of 35 mm cameras (Nikons). Before committing the final scene to film, he would check all his exposure settings by taking some Polaroid instant films. He even said in 1981 that he had not used an exposure meter for over twenty years. Mind you, with seasoned pros such as Parkinson, he would have been able to guess the settings and be spot on over 90 percent of the time, though “about a fortnight at f8” was only said in jest.

Whilst he is best remembered for his fashion work, Parkinson was also a very skilled portrait photographer. With regards to this type of work he said, “I try to make people look as good as they’d like to look, and with luck a shade better. If I photograph a woman then my job is to make her as beautiful as it is possible for her to be. If I photograph a gnarled old man, then I must make him as interesting as a gnarled old man can be,” Norman Parkinson, a true professional. He said that to be a good photographer you need to be “a journalist who uses his nut.” We can all still learn from Parky.