A good many years ago, I had my first encounter with pizza, when one of my college friends suggested we eat at an Italian place in London’s South Kensington. It was a simple café and almost next door to South Kensington underground station. Every few minutes the vibrations of the underground trains could be felt, clattering along somewhere beneath the floor. My friend had suggested that we order pizza, but I had absolutely no idea what to expect. This was in the days before the pizza chains appeared and although pizza had been introduced into Britain decades earlier by Italian immigrants, it was little known or understood outside the close-knit Italian communities. At the time, I had the curious impression that a pizza resembled a small pyramid, which was partly covered with cheese. At least, I was right about the cheese.

When the pizzas appeared on the table, it was something of a revelation. I was hooked immediately. I had always been passionate about cheese – even as a teenager – but the pizza combined everything that I adored: a magical aroma of herbs, a rich tomato base, a blend of contrasting savoury flavours and a variety of colours and textures. As a result of that experience, I became a pizza enthusiast, and ever since I’ve sought out pizza almost wherever I went. Some years later, I called into a simple workers’ café just outside London and was amazed to see Pizza Napolitana on the menu. Suspending my disbelief, I ordered one and was slightly taken aback to receive a plate of cheese on toast with a slice of tomato on the top.

In 1965, the entrepreneur and pizza enthusiast Peter Boizot opened the first Pizza Express in London. After working and traveling in Europe for ten years, he discovered what genuine pizza should taste like. Realizing that London couldn’t offer authentic pizza, he brought an Italian pizza oven back to England, together with a chef from Sicily. Peter Boizot opened his first pizzeria in London’s Wardour Street. It was an appropriate place to start because at the time, Wardour Street was the centre of the British film industry and the home of several major music publishing companies. The demand for pizza flourished. And because of the character of the restaurants and the authentic Italian taste of the pizzas, so did Pizza Express. Today there are five hundred branches across Britain and a hundred more in other countries.

In 1973, the American Pizza Hut company appeared in Britain and expanded rapidly. When I first visited Thailand in 1987, I was amused to see an enormous Pizza Hut sign standing proudly above the rooftops of Bangkok. On my first evening in Thailand, it was a relief to find an Italian restaurant not far from the hotel. Not an adventurous start I admit, but I knew almost nothing about Thai food and I was feeling jaded after a long flight. I ordered a pizza, which I so often do. During the meal, an over-powering feeling came over me, which was both moving and somewhat unsettling. Gazing out of the restaurant window at the evening traffic lumbering slowly along Sukhumvit Road, I had an overwhelming feeling I that I had finally come back home. Never for a second, did I realise that I was glimpsing the future.

Pizza is a type of flatbread and shares its ancestors with countless varieties of flatbreads, among them Scottish bannock, Greek lagana, Turkish pita, Alsatian pissaladière and Indian roti. The history of this sprawling family goes back to the time when people learned the secret of mixing flour and water then heating the dough on a hot stone. Archeologists have discovered that flatbreads have been around for at least 7,000 years and evidence has been found ancient Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt and the Indus civilization. Flatbreads originated in the so-called Fertile Crescent, an area where agriculture developed and which includes modern-day Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine and Syria. In his entertaining book A History of Pizza, Dr Alex Bugeja describes how in the 6th century BCE, Persian soldiers ingeniously baked flatbread on their shields by holding them over an open fire. In ancient Rome, Focaccia was a kind of proto-pizza, a flatbread known to the locals as panis focacius, to which various toppings were then added.

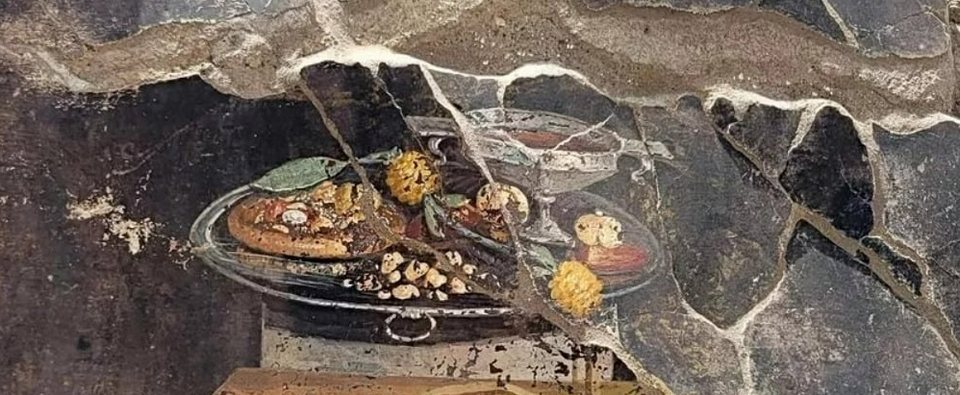

In 2023, archeologists discovered a fresco on the wall of a house in Pompeii that depicts a kind of flatbread that might have been an ancestor of pizza. The city of Pompeii, you might recall, was destroyed after a catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. The city was only about fifteen miles from Naples, the traditional home of pizza. In the early 16th century, an early type of pizza was sold in the taverns and on the streets of Naples and proved a cheap and a popular meal. It was made without tomato sauce, because tomatoes were unknown in Italy before the mid-16th century. Tomatoes originated in South America and were brought to Europe by Spanish explorers. They were then brought to Italy via the Kingdom of Naples, which at the time was under Spanish rule.

The dish that you and I would recognize as pizza gradually evolved from the mid-sixteen century onwards. The first known pizzeria, Antica Pizzeria Port’Alba, opened its doors in Naples around 1738. In 1843, the city was visited by Alexandre Dumas (he of The Three Musketeers) and he commented on the diversity of pizza toppings available.

One of the early styles of Neapolitan pizza was the Pizza Marinara (Sailors’ Pizza) which was made using olive oil, tomatoes, basil, oregano and garlic. Oddly enough, no cheese. It was ideal for cooking on long sea journeys, because it was made from easily-preserved ingredients. Pizza Margherita dates from 1889 and traditionally uses San Marzano tomatoes, fresh buffalo mozzarella and fresh basil leaves to bring an aromatic touch. Legend has it that the pizza was created in honour of the visiting Queen Margherita of Savoy. Italy has several well-known pizza styles. The classic Neapolitan pizza base is soft and pliable with the characteristic burn marks of the wood-fired oven, whereas the Romans generally prefer a thin and crispy base. I once visited a restaurant in Florence and was surprised to see that the pizzas were baked in large rectangular trays and sold by portion.

Pizza has come a long way since its inception in every sense of the word. I once tasted a superb authentic pizza at an Italian restaurant in the Mexican city of Acapulco. On another occasion, I had an outstanding Pizza Margherita at a delightful beach-side restaurant in the little town of Sanur, in south-east Bali. My intention was to eat nasi goreng, for I always enjoyed Indonesian food, but seeing a genuine Italian wood-fired pizza oven, presided over by an Italian pizzaiolo (from Sicily, it turned out), my mind was quickly changed. The nasi goreng could wait.

What you drink with pizza is entirely up to you. A cup of coffee or a beer will do I suppose, if that’s what floats your boat. In Italy, wine has always been the traditional accompaniment and to my mind, pizza cries out for wine. I used to be a frequent customer at one of original Pizza Express restaurants, which is a stone’s throw from the British Museum. It’s on the corner of a dark, narrow street that probably hadn’t changed very much since the time of Charles Dickens. On one occasion, an earnest young Spanish waiter informed me that because there were some slices of mushroom on my pizza, I should drink white wine, rather than red. This of course was complete nonsense, and exuding as much sweetness and charm that I could muster, I told him so.

The dominant flavour of the traditional pizza is usually the savoury umami flavour of the tomato sauce, and it partners well with almost any crisp, dry, red or white wine. In days gone by, the people in Naples would probably drink whatever wine happened to be available. There would have been plenty of choice, because Naples lies in Italy’s Campania region where wine has been produced since the 12th century BC. One of Italy’s most ancient wine regions, it supports a vast array of grape varieties, some of which are found nowhere else on earth. Wines from Campania tend to be fruit-forward and youthful and make perfect matches for pizza. Unfortunately, you’d be hard-pressed to find Campania wine in these tropical parts, so let’s look at some alternatives.

The ideal pizza wine is what the Italians call vino da pasta, a generic name for any inexpensive light table wine and usually served on the cool side. Almost any light Italian wine will work well with pizza. A Valpolicella is a classic accompaniment, though not a Valpolicella Superiore Ripasso, because the pizza would be overwhelmed by the wine’s complex flavour. Bardolino is red and light with a tart acidity that would contrast well with the mozzarella cheese. If you prefer white wine, a crisp dry Frascati or Soave works well. A chilled, dry rosé would also be an excellent choice. If you like something a little more assertive, a Chianti is another good candidate because of its savoury, herbal hints that come from the Sangiovese grape. There’s no need to choose a white wine just because your pizza has a few bits of chicken on the top. It’s the dominant flavours that matter. But if you are having a seafood pizza, a Sauvignon Blanc would be a good choice. Pizza Tonno features a topping of tuna fish but this has enough flavour to match a light red or more assertive dry white.

Perhaps you might finish up, as I so often do at home, with something more modest out of a box. But I’ll let you into a secret, if you promise not to tell anyone. Blending is a quick and easy way to enhance the taste of ordinary wine. Even the ubiquitous Mont Clair or Peter Vella brands can be elevated to greater heights. When you are sure that nobody is watching, pour the cheaper wine into a large carafe or jug, then add about a glass of the better-quality wine of the same colour and style. The ratio is roughly about 1:7. Give the blend a gentle stir to mix thoroughly and let it rest for twenty minutes or so. You’ll probably be surprised what a difference this process makes. You see, the mediocre wine, realizing that it’s in the company of something more sophisticated, tends to take on some of the characteristics of the better wine. Unfortunately, this phenomenon rarely occurs among humans. Just be sure to keep this trick to yourself, otherwise you’ll be off my Christmas list.