PATTAYA, Thailand – It’s not often you hear two virtuoso concert pianists in a single recital. San Jittakarn and Anant Changwaiwit are young and highly-experienced Thai pianists both of remarkable talent and musicianship. A few days ago, Anant wrote, “San and I have been close friends for over eighteen years, yet this will be the very first time we have had the opportunity to share the stage together.” They certainly impressed the enthusiastic audience at Ben’s Theater Jomtien with a fascinating programme of dazzling piano works by three composers renowned for their piano music.

Robert Schumann wrote some of the most evocative and sometimes perplexing works of the mid-nineteenth century. He was born in 1810, when Beethoven was already an established forty-year-old composer, and when the Austrian Franz Schubert was just a boy of thirteen. Schumann became an influential figure in Germany and his music pushed emotional, structural and musical boundaries to extremes. Often inspired by literature, his music could be dramatic, obsessive and tumultuous; it sometimes drew on biographical themes, reflecting his profoundly unsettled life which eventually left him fighting the demons of mental illness. In his day, Schumann’s music must sometimes have sounded modern and progressive especially to the older generation. He sometimes baffled music critics, one of whom wrote, “everywhere there are only bewildering combinations of figurations, dissonances, transitions and in brief, torture.”

These scathing comments would hardly apply to Schumann’s delightful Arabesque written in 1839. Despite the name, there is no connection with Arabic music: the word arabesque was often chosen by composers to suggest a florid and flowing style reminiscent of Arabic decoration. Many other composers wrote pieces described as arabesques, notably Debussy, Granados and Sibelius. In the autumn of 1838, Schumann left his German home in Leipzig for Vienna, the thriving Austrian capital city which at the time, was undergoing intensive industrialization. But despite the animated and lively atmosphere, Schumann found that he was beset by depression and disappointment.

It’s surprising that under the circumstances, he produced this light and charming piece. Thoughtfully performed by San Jittakarn, this short work opens with a delicate flowing melody, which San played with a sensitive awareness of phrasing and measured use of rubato, a musical technique in which the performer subtly varies the tempo for expressive purposes. I enjoyed San’s performance tremendously for he played with a “sense of line” and brought out a lovely luminous tone quality from the Yamaha piano. The slower section of the piece in E minor has a powerful yet yearning melody which San brought forward splendidly. Later, a chromatic section brings us back the rippling melody that started the piece. At the end, a broad, lingering and reflective melody draws the work to a close. I was impressed with San’s excellent sense of timing, an expression that we don’t often use in music, but which means the sense of “placing notes” at precisely the right moment for their most evocative and emotional effect.

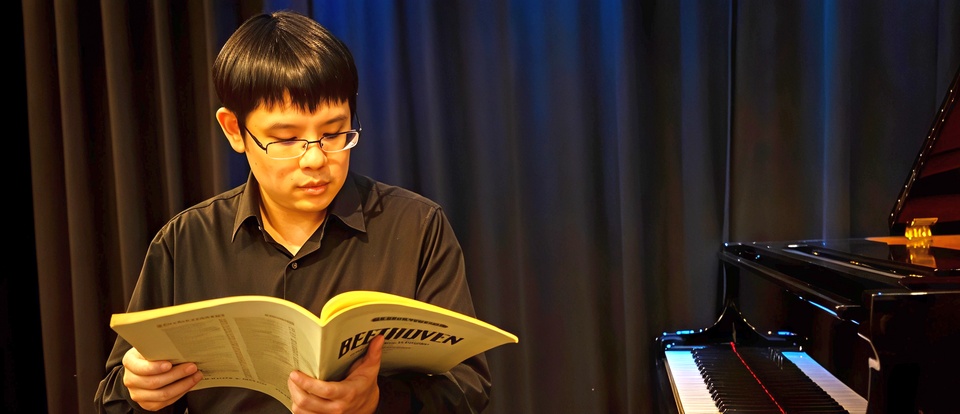

San’s experience as a pianist shone through clearly in his performance of this piece. In 2018, he was among the winners at the Geneva International Music Competition; he was the first Thai recipient of the Paderewski Prize and successful at the Maria Canals (not Callas!) International Music Competition in Barcelona. He has been successful in many other music competitions and was the first Thai pianist at the International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw. He has also appeared with the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande and broadcast in Belgium, Switzerland and in the United States. San attained his Bachelor’s degree at Oberlin College in America and continued his studies at the Juilliard School and Yale University.

With barely a pause, San then launched into Schumann’s technically challenging Symphonic Etudes, written in 1834 when the composer was still living in Leipzig. As the name implies, the work is a set of studies. Each of them is a musical variation on a hymn-like theme heard at the start. Interestingly, the work is dedicated to the English composer William Sterndale Bennett, who was six years younger than Schumann. They had met in Leipzig in the late 1830s when Bennett was there for several extended visits. He and Schumann evidently got on well together: they went on long country walks during the day and visited the lively local taverns by night. Bennett evidently had some reservations about Schumann’s music, which he confided to a friend, seemed “rather too eccentric”.

Symphonic Etudes opens in the dark key of C sharp minor with a somewhat gloomy melody which forms the basis of the variations that follow. San gave a brilliant and compelling performance of the work. The first variation fairly skips along and San highlighted the moments of darkness and foreboding especially when the melody was heard in the bass.

As so often with Schumann, Symphonic Etudes contrasts funereal moments of desolation with passages of gentle playfulness, or moments of wistful longing. Sometimes lyrical passages are contrasted with high drama or pounding chords, like a bizarre circus march. This is the kind of music that must have confused Schumann’s critics as well as William Sterndale Bennett. San played Etude 2 with passion, yet perfectly controlled repeated chords in the left hand. Etude 3 with its rapid staccato arpeggios, was brilliantly played. Etude 5 is marked Scherzando and San brought out the airy lightness of the piece and really caught the ethereal spirit of the music. I was impressed how in Etude 6 he brought out the melody from the rush of notes in the flowing accompaniment. Etude 9 is marked “Presto possible” which means something like “play as fast as possible”. San certainly did, and hurtled through the maze of notes at a tremendous speed, yet remaining perfectly in control throughout. Etude 10 was played with exceptional energy and San brought out the staccato melody above the tricky chromatic bass line superbly.

In contrast, Etude 11 is a wonderfully expressive and haunting melody played over a shimmering arpeggio accompaniment and typical of the way Schumann combines different moods at the same time. I relished the way San brought out the perfectly phrased, elegant melodic line, contrasting it with the strangely unsettling accompaniment. The Finale, Etude 12 returns the music to a more joyful mood but contains difficult passages and awkward stretches for both hands. San brought the music to life through his natural sense of musical expression, his careful phrasing and his use of dynamic contrast. He drove the music relentlessly to its heroic conclusion. It was a brilliant performance. In November this year, San will take part in The 43rd Yokohama International Piano Concert in Japan, where he will play the same programme.

The second half of the concert featured two extraordinary pieces performed by Anant Changwaiwit. They are considered the most difficult in the piano repertoire: Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit and Balakirev’s Islamey. And there’s an interesting connection here. For many years, Balakirev’s piece had been regarded as the most difficult work in the piano repertoire. Ravel admitted to fellow composer Maurice Delage that he wanted to write a work which was even more challenging than Islamey. Ravel wanted to out-do Balakirev. “But perhaps I got a bit carried away”, he later reflected. Perhaps he did. Ironically, Gaspard de la Nuit contains some passages that Ravel couldn’t manage himself.

The three-movement suite was published in 1909, though listeners are sometimes puzzled by the enigmatic title. The name Gaspard is derived from the Persian word for “someone in charge of the royal treasures.” The title therefore implies someone in charge of the night-time, the guardian of dark and mysterious forces and all things distinctly creepy. From the first few notes, once can sense the haunting atmosphere and the presence of unworldly spirits and later, demonic creatures and the spectre of death. And yet, the sound-landscape of the music is unmistakably Ravel.

The opening movement, entitled Ondine was inspired by a poem about a malevolent water-nymph. Anant caught the magical and ethereal atmosphere perfectly with beautiful phrasing and set the mood of the piece. Despite the difficult and awkward fingering, he made the atmospheric music sound effortless. The sombre second movement is entitled Le Gibet and evokes the image of a corpse hanging on the gallows in the early evening, as the sky reddens in the glow of the setting sun. Throughout the movement, the note B flat sounds continuously and accompanies a slow and slightly menacing chordal melody. The repeated B flat represents a bell, tolling for the hanged man. Anant really brought out the haunting, soulful and timeless quality of this strange, spectral music. Even at this slow tempo, playing the work is a technical challenge, because there are so many musical elements at work. It would be tricky even if the pianist had three hands, with seven fingers on each. Anant played the movement fluently and captured the dark, oppressive nature of the music. His placing of the repeated “bell” notes was perfect and brought a sense of desolation to the music. The lonely, unaccompanied B flats at the end of the piece left a strange sense of loss. It was a remarkable performance.

The final movement, entitled Scarbo is the most technically and musically challenging. Ravel piles up the challenges relentlessly: notes rapidly repeated, leaps around the keyboard that must be perfectly even, lightning-fast passagework played almost inaudibly and strangely spooky chromatic scales. The movement is inspired by the vision of a devilish goblin, a hideous creature of the night that scuttles and scampers about in the murky gloom, casting distorted shadows in the moonlight. The music is bizarre, tortuous and at times positively scary and Anant really brought out these qualities in his meticulous playing and range of expression. The extremely difficult rapidly-repeated notes that dominate the movement were brilliantly played with superb articulation and clarity. The music hurtles towards its close and then, suddenly and insouciantly, tails off as though it were all part of a wild and feverish dream, now gone. Anant brought a remarkable sense of tension to the music, perfect timing and a sense of relentless quivering and frightening energy. It was a stunning performance. Anant will perform the work again on 2nd November at the Thailand International Piano Festival.

Since 2014, Anant has performed regularly as a concert soloist with several orchestras. He has performed Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 1 with Thailand Philharmonic Orchestra, Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No.1 with North Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with the TPO and the Saint-Saëns Piano Concerto No. 2 with the Mahidol Symphony Orchestra. He has frequently appeared in concerts and festivals with artists from Europe, USA and Asia and performed at the Thailand International Composition Festival, the Thai-Japan Contemporary Music and the Chiang Mai Ginastera International Music Festival. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Classical Music Performance from College of Music, Mahidol University with Gold Medal scholarship and Merit Scholarships. During his university years, he was a winner of the 4th Thailand Mozart International Piano Competition and one of the four Gold Medal winners from the 16th SET music competition.

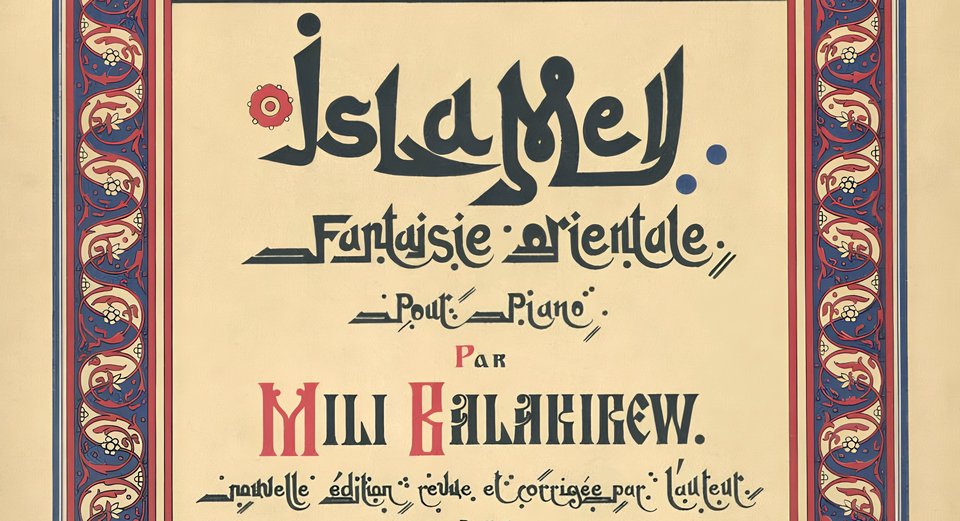

The concert ended with Anant’s truly heroic performance of Balakirev’s Oriental Fantasy entitled Islamey. Although his music is rarely heard today, Mily Balakirev was a prominent Russian composer, conductor and pianist. He was a mentor to many younger Russian musicians but his personal manner could be tactless and he was not sympathetic to those whose ideas did not concur with his own. He particularly disliked the music of Wagner and in a letter to a friend in 1868, he wrote “After seeing Lohengrin, I had a splitting headache and all through the night I dreamed about a goose.”

Islamey was written in 1869, nine years after the composer had made a trip to the Caucasus, the geographical area that lies between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. The region contains parts of present-day Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Like many of his Russian contemporaries, Balakirev was passionately interested in national folk songs and folk melodies. Islamey is based on three musical themes. Balakirev heard the first two on his trip to the Caucasus and the third was taken from an Armenian folk song that the composer heard at a recital at Tchaikovsky’s house, in the summer of 1869. Although Balakirev was a virtuoso pianist, he admitted that there were passages in Islamey that he couldn’t really manage. The Russian composer and pianist Alexander Scriabin seriously damaged his right hand when he was fanatically practising the piece.

Marked Allegro agitato (“fast and agitated”) the piece begins with rapid repeated notes which gradually becomes more frenetic as the music wanders through difficult key changes. Even so, it is joyous stuff and Anant brought out the quality of the music with brilliant articulation, perfect rhythmic control and a captivating sense of joie de vivre. There are some lovely reflective passages in the music especially the second theme which has a flowing, yearning and even heroic quality which Anant reflected perfectly in his sensitive and thoughtful playing. But it’s not long before we are back on musical race-track at a furious tempo. Like a Formula 1 racing driver, Anant kept up the pace throughout, with perfect phrasing, superb articulation and energetic drive that few other pianists could ever dream of matching. It was a brilliant and stunning performance that could only be described as phenomenal.