by Chalerm Raksanti

Bali hangs like a glowing emerald in the necklace of

the Indonesian archipelago. Lava-flanked peaks, two of them active, roof

the islandís ninety mile length. Streams tilt down slopes shingled with

fertile rice paddies. Though Java lays only a mile away, fierce currents

and reefs long isolated Bali. This isolation favored the development of

its distinct culture.

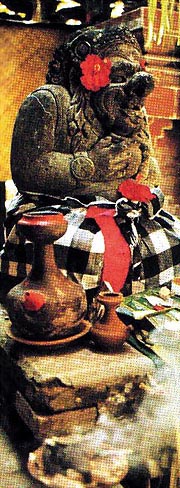

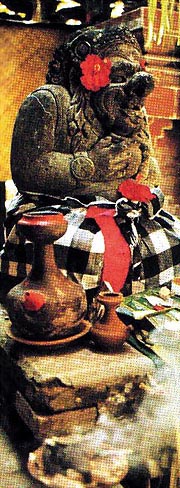

Preparation

for tooth filing ceremony

Preparation

for tooth filing ceremony

Spiritual values are the strongest motivating force of

life on the island, and prompt the exuberant festivities which punctuate

most of Balinese life. Their religion is a complex and imaginative blend

of Hinduism, animism and ancestor worship. Hinduismís deepest inroads

into Baliís animism came in the 16th century, after the armies of Islam

had defeated the powerful Madjapahit Hindu dynasty. In East Java the weak

Hindu princes capitulated, but the undaunted fled across the mile-wide

strait to Bali, accompanied by musicians, poets, dancers and artists.

Within a century, Dutch explorers, lured to the East

Indies by spices, built a commercial empire in Indonesia. Baliís

treacherous reefs and unpredictable currents caused these voyagers to sail

on safer shores. Thus insulated, the seeds of Javaís transplanted Hindu

culture took root and flourished for almost 400 years in Bali under the

refugee princes who carved up the island into tiny kingdoms. The Balinese

culture endured a history fraught with turbulence and violence. It has

weathered a Dutch domination, Japanese occupation during WWII, the war of

Indonesian independence, and the bloody foiling of a Communist coup

attempt.

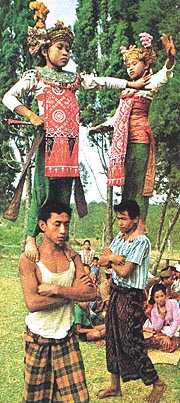

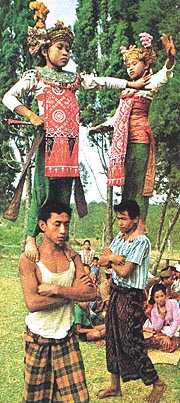

Deity

dressed for a part

Deity

dressed for a part

Today Bali faces the invasion of tourists; what the

Balinese call the Ďjet invasioní. But for the romantic sojourner, it

is still possible to seek out Baliís special moments. Paradise (like the

visions or dreams which inspire us to create such a concept) lies in the

eye and the mind of the beholder. More than just a place, Bali is an

impression, a feeling and an experience. Roaming through Baliís

rice-rich heartland, the visitor can trek through wild scrub jungle in the

west, up to the limestone cliffs at the southern tip of the island, and to

northern plantations of coffee and coconut. And along the back roads of

this tropical jewel, the Balinese will welcome you. But whatever they are

doing, they do for themselves, and not for your entertainment.

One ancient custom which is still practiced in the

villages is the tooth filing ceremony. The joyous ritual, performed for

both sexes, protects against the evil in human nature. This is a ceremony

which marks the coming of age for pubescent youngsters. A priest rubs a

gold ring on the boy or girlís mouth, and then he wields his tapered

file until he grinds down the six upper front teeth until they are all

even. The event is nerve wracking, but almost painless.

Balinese life is influenced by innumerable gods and a

rich tapestry of occult and the mysterious world of the unseen. Many of

their festivals are extravaganzas for the gods. Women of Tulikup, a

village near the southeast coast, thread their way through a palm-ached

pathway bearing offerings of good and flowers on a three mile march to the

sea. Behind them, a snake-like column that stretches across a mile of rice

paddies, men bring images of deities from the village temple for an annual

cleansing in the Indian Ocean. This done, the islanders will joyously

feast on the offerings of duck, rice and fruit.

Trance

dancers

Trance

dancers

Young girls from the village of Kintamani, in the

shadow of the smoldering volcano Batur, perform the sanghyang deling, a

trance dance. This is one of the rituals that dramatize the villagersí

constant awareness of the supernatural world. As a chorus chants to a

flute and drum, older women choose certain girls whom they believe are

particularly receptive to the influence of the gods. A mystic priest

prepares a brazier of burning incense, and puppet masters manipulate two

sacred puppets, making them dance. Soon the girls are transfixed and grow

drowsy. Their eyelids droop and they slide forward and, at last, deep in a

trance, they begin a dreamlike dance, gliding and twirling, oblivious to

everything around them. They shuffle barefoot through a bed of smoldering

coconut shells. Then the priest frees, unhurt, from the spell.

It takes only a brief encounter with the menacing surf

gnawing at Baliís coastline to understand why the Balinese regard the

sea as the domain of their demons, and why their gods choose to dwell in

the mountains. Of course demons pose no threat to tourists who flock to

the beaches in droves. But most tourists only travel paved roads, which

bypass the small villages to avoid overwhelming the quiet local life.

Balinese culture is stronger than the tourist.

![]()

Preparation

for tooth filing ceremony

Preparation

for tooth filing ceremony Deity

dressed for a part

Deity

dressed for a part Trance

dancers

Trance

dancers