When localizing the global economy to nation-state level, there is understandably often a clear link with a country’s history. Despite its modernization, Thailand has such a link, which to a large extent explains its middle-income trap.

Still a rural economy

To start with, the kingdom has retained significant vestiges of its feudal past; after all, slavery and serfdom were only abolished in the 20th century. Until then, this meant a shortage of labour (most Thai men were courtiers, military or slaves) and social immobility, which inhibited entrepreneurism.

Despite prohibition of rice and other agricultural exports for many years, Thailand remained an agrarian economy. The importance of the economic contribution of agriculture to the economy has now started to wane and less people are employed in agriculture. However, Thailand remains by a very significant margin the least urbanized economy for a country of this size at this stage of development. This, along with the continued abundance of essential resources, may explain the lack of impetus for the kind of development that the trading hubs of Singapore or Hong Kong enjoy.

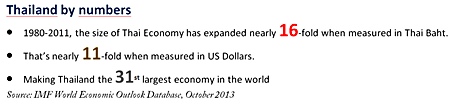

Until this is resolved, then, despite the best efforts to reach more sophisticated levels of socio-economic development – via IMF-endorsed development programmes like Export Oriented Industrialization (EOI) and Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI) – the foundations that the edifice is built on remain fragile. To some extent this fragility has been hidden by the fact that the Thai economy appears to have grown well during the last 30 years or so.

1997 and all that

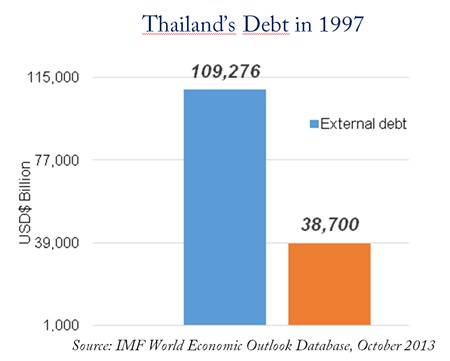

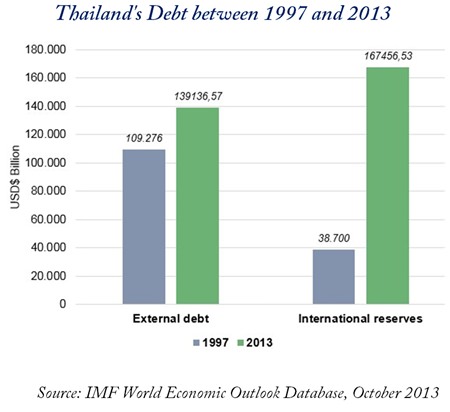

Thailand’s economic growth came at a price that suddenly had to be paid in 1997 when Thailand suffered the consequences of having accumulated international liabilities that dwarfed its international reserves.

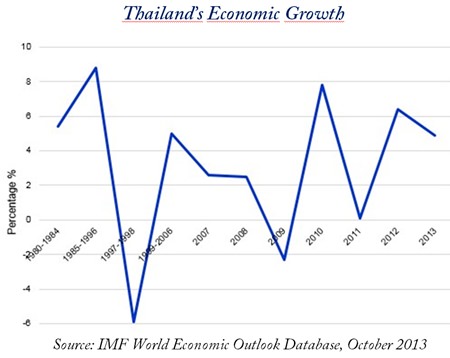

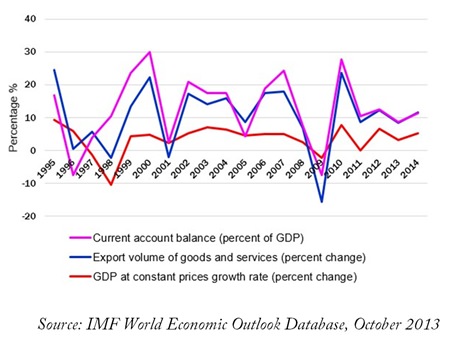

This goes some way to explaining Thailand’s volatile growth pattern over that same period – where growth was highest in the period during mid-1980s to late 1990s, until a fall in exports exposed the structural problems even more – despite the export volumes Thailand had become over-dependent on foreign liquidity and credit. The “Thailand’s Economic Growth” chart on this page shows the volatile pattern clearly.

Although there have been some recoveries since the 1997 collapse, the pattern still looks very fragile.

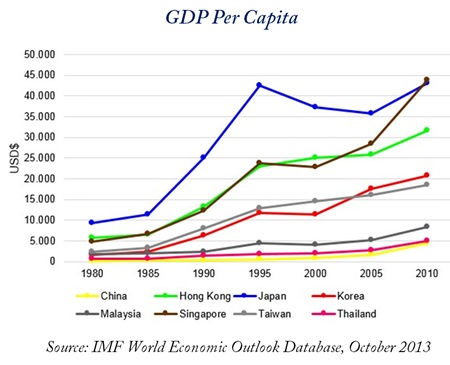

Yet that’s not the only problem: if we look at the development in GDP per capita versus other Asian countries over the same period, Thailand is a clear laggard (along with China), bogged down in the middle income trap because of the inability to match the GDP per capita achievements of Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Korea, Taiwan and most worryingly, Malaysia.

Thailand today

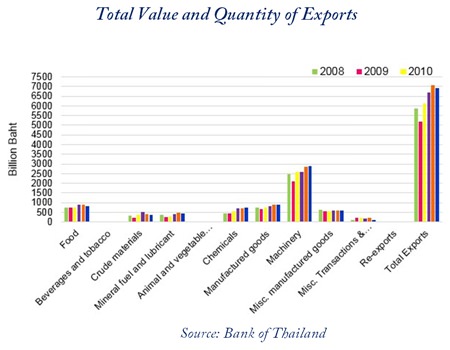

Thai GDP still remains largely export-driven as does the current account; although the lessons learned from 1997 have reduced reliance on foreign funding. The financial management of the economy has improved and become more responsive to market demands.

However, export reliance remains a dangerous game, especially when its performance is as volatile as Thailand’s, which largely reflects that, apart from one or two outstanding successes, such as automotive, it is still focused on exporting the wrong goods at too low a value to the wrong buyers.

The future

Notwithstanding the financial system’s greater stability, the big problem facing Thailand continues to be the socio-economic development hiatus that has resulted in the inadequate emergence of a highly-skilled urban workforce, escaping the middle income trap to become affluent consumers. Although the numbers employed in the agricultural sector continue to fall, this is not driven by any impetus to urbanize or industrialize. Without this it remains difficult to see how Thailand can develop a wide range of globally competitive businesses, despite the best efforts of supportive organizations like the Board of Investment (BoI).

Solve that problem and you can really address how best to create a much more harmonious society with higher levels of income and wealth to better distribute. Without solving that, it looks increasingly difficult to bridge the ever-widening political divide, with the looming nexus of interwoven political, social and economic issues.

Ironically the very factors that made firstly Sukhothai, then Ayutthaya and more recently Bangkok the hub of such a sufficient federated society also rendered each of them less motivated to break the shackles of socio-economic stasis. In the Sukhothai era the focus on individual and state survival was the primary issue. In Ayutthaya the lack of development was overcome with the short term fix of imported mercantilism. In the last century, the reliance was on imported capital.

Those same factors continue to inhibit modern Thailand developing in the same way as neighbours who have had to overcome the lack of natural advantages with which Thailand was blessed but which, in developmental terms, now seem to be more of a curse. There is a fine line between sufficiency and complacency but many of the societal failings of modern Thailand reflect the fact that for too much of its history, this land of plenty has been content to rest on the laurels given to it in abundance by nature.

My difficulty is that I don’t see anything that is likely to change that without a very dramatic sequence of events which may involve experiencing a very challenging period of transition. The current political situation may or may not be the precursor to that but either way transitions of this nature tend to be very difficult experiences for all involved.

However, there are silver linings – let us not forget that socio-economic development will be underpinned by the success story that is the modern Thai financial system. The fear of excess that has permeated since the 1997 crisis continues to ensure that Thailand’s banking system is well run and its capital markets well regulated. The financial reforms that have taken place then have created a solid foundation on which to build socio-economic reforms – despite the political stress.

Thai capital markets look to be offering reasonably attractive value as soon as the political divide is bridged and the vast majority of short-term ‘hot’ foreign capital has already fled the country. The much better reserves-to-debt ratio means that a repeat of 1997 is not on the horizon, despite what some commentators may say.

Thailand may not be developing in a way that enables the country to realize its potential and may have some very unpleasant growing pains still to go through but at least Tom Yam 2 the sequel is unlikely – debt has fallen dramatically and yet reserves have increased in the 17 years since the crisis.

| Please Note: While every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is correct, MBMG Group cannot be held responsible for any errors that may occur. The views of the contributors may not necessarily reflect the house view of MBMG Group. Views and opinions expressed herein may change with market conditions and should not be used in isolation. MBMG Group is an advisory firm that assists expatriates and locals within the South East Asia Region with services ranging from Investment Advisory, Personal Advisory, Tax Advisory, Private Equity Services, Corporate Services, Insurance Services, Accounting & Auditing Services, Legal Services, Estate Planning and Property Solutions. For more information: Tel: +66 2665 2536; e-mail: [email protected]; Linkedin: MBMG Group; Twitter: @MBMGIntl; Facebook: /MBMGGroup |