Die Hard, with a vengeance (continued)

Tim Price, Director of Investment PFP Wealth Management

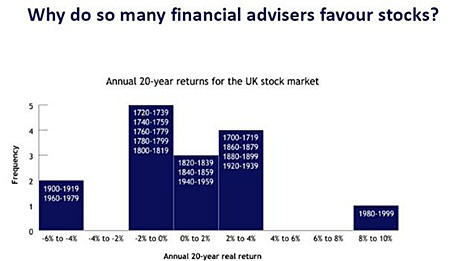

“Equity myth”? Isn’t that somewhat harsh? Not really. Consider the following chart, which we have demonstrated before. It shows the annualised 20-year returns from the UK stock market over three centuries: the 18th, 19th and 20th.

Three aspects of the chart are worthy of emphasis. Firstly, it looks much like the standard ‘bell curve’ – which is what you would expect, but only over the very long term, a term realistically much longer than the typical investor’s timeline. Results cluster around an average return.

Secondly, and more alarmingly, those average returns are dramatically lower than equity market propagandists would have you believe. The median real annual return from UK stocks, over a period of three centuries, broken down into smaller, 20 year durations, is approximately zero. Not only is “stocks for the long run” a ridiculous thesis, but the long-run return has had, if history is any guide – and it is our only guide – a tendency to be vanishingly small. Perhaps the riskiness of the stock market is understated in popular conception?

The third observation is, to us, the most striking.

It certainly answers the question posed in the title: why do so many financial advisers favour stocks? Answer: because the chances are, those advisers all worked at least some stage during the last twenty years – the one period on the entire chart during which the annual 20-year real return from the stock market was meaningfully large, at between 8% and 10%.

To put it another way, the 1980-1999 experience was, in the context of the past three centuries, unique. To put it another way, the 1980-1999 equity market return was a 1 in 15 phenomenon. It was most certainly not the norm. But the fund management industry, with its perennial obsession with equities over any other form of asset, certainly behaves as if it was the norm. As the regulator insists, past performance is not necessarily any guarantee as to future returns. Equity market apologists today must fervently wish that to be the case.

(Source: Global Financial Data, Datastream.)

Of course, the problem with statistics is that if you torture them for long enough, you can get them to confess to anything.

Since we’re not in the business of promoting funds [either equity funds or those of any other kind] we can speak with some degree of objectivity about the current make-up of the investment landscape. Whatever else it can be said to be, it is extraordinarily polarised. Stocks continue to bounce around in a largely trendless way, but the recovery/dead-cat bounce off the lows of March 2009 is undeniable. Government bonds, on the other hand, notably those within G7 markets, are predicting nothing less than deflation. There is no other way to interpret two-year US Treasury notes yielding 0.5%.

The trend is undeniable. From a yield of almost 7% at the start of the decade, US yields have trended relentlessly lower, approaching 2% during the panic phase of the crisis in 2008, and sitting at around 2.75% today, and still trending downward. Other major government bond markets have delivered similar performance. But the historical precedent of one of those markets is the most instructive: that of Japan.

Japan was ahead of the West by almost 20 years. The seeds of its own property market and banking collapse were sown in the 1980s, and by the late 1990s the country was already floundering in deflation. Note also that the process of quantitative easing, the second iteration of which now threatens in the other industrialised economies, has achieved little by way of meaningful positive impact in Japan. At the risk of labouring the message about equities, Japan’s Nikkei 225 Index is currently 75% below its bubble era high, reached some 21 years ago.

US 10 year yields, last 10 years

Here is the chart of 10 year US Treasury bond yields over the past decade. (Source: Bloomberg LLP.)

To sum up, then: The banking and financial services industry routinely overstates the performance and, indeed, relevance of exclusively long-only equity investing. This would be understandable if it were a message coming solely from stockbrokers, but is more galling to be being transmitted from institutions that should be asset class agnostic.

The investment media, by and large, assist in this equity-centric propaganda. This is not to be simplistically critical of the idea of owning common stocks per se, but it is meant to be critical of an entirely equity-centric portfolio at a time when the likelihood of a full-blown deflation has not been higher since the 1930s – in western markets at any rate. This argument also underlines the admittedly longer term equity case for investment in the fundamentally more attractive emerging economies.

To add kerosene to the tinder box, governments have not stood entirely idly by. Heavily influenced by the neo-Keynesian addicts to stimulus irrespective of sovereign solvency, Western administrations, led in no small part by the US Federal Reserve, have thrown everything at their disposal by way of taxpayers funds to try and ensure (vainly, thus far) that economic recovery will soon return – in much the same way that our ancient ancestors used to make human sacrifices to placate the gods of the harvest. While it has brought recovery no closer, it has managed to utterly distort the pricing signals of the financial markets and guarantee a foggy mixture of moral hazard and general economic confusion. Perhaps, as in the case of a forest fire, it might be better to let the conflagration burn itself out and allow the forest to prepare for cyclical re-growth.

Japanese 10 year government bond yields,

1990 to present day

(Source: Bloomberg LLP.)

James Rickards nicely identified the problem of “moral hazard creep”, writing in a recent Financial Times: “Policy, whether it be printing money, guarantees or deficit spending, can prop up asset values for a while. This may even be useful in a liquidity crisis. But a solvency crisis is another thing. The longer policy distorts markets by ignoring fundamentals, the longer those reliant on market signals will sit on their hands [investors: this means you]. The Fed’s recent decision to continue asset purchases shows there is no exit once this path is chosen. As we approach the second anniversary of the Fannie and Freddie bailouts, are we better off? Values cannot recover until they first hit bottom. In short, our economies would be growing more robustly today if we had taken our medicine in 2009.”

No use crying over spilt milk, though. From the perspective of today’s investor, the answer must surely be: diversify across multiple asset classes as appropriate, and keep some powder dry.

The above data and research was compiled from sources believed to be reliable. However, neither MBMG International Ltd nor its officers can accept any liability for any errors or omissions in the above article nor bear any responsibility for any losses achieved as a result of any actions taken or not taken as a consequence of reading the above article. For more information please contact Graham Macdonald on [email protected]