When I was a teenager back in The Old Country, I once had a brief but overpowering desire to play the trombone. I borrowed one from school and took it home for the holiday and with the help of a tutor-book, learned to play a selection of simple tunes. But that was as far as it got and my affair with the school trombone was somewhat short-lived. It seemed that the trombone and I simply were not made for each other. I returned to the cello and never attempted the trombone again.

When I was competent enough as a cellist to join our county orchestra, I was shocked to discover that the trombone players of the orchestra were an uncouth bunch of stocky teenage lads, all of whom looked like farm-hands. Perhaps they were, because we lived in the country. A few years later, when I played in larger orchestras, it always seemed that the brass players were a rough-and-ready macho male crowd. I often wondered whether their assertive character attracted them to brass instruments, or whether they gradually acquired this persona by playing them. Perhaps a bit of both. In many orchestras, the woodwind and the horn players are invariably rather more refined types. String players incidentally, consider themselves the most sophisticated individuals in the orchestra. However, a professional trombone player once remarked to me that he and the other brass players regarded the strings as a bunch of dim-witted sheep who sought safety in numbers.

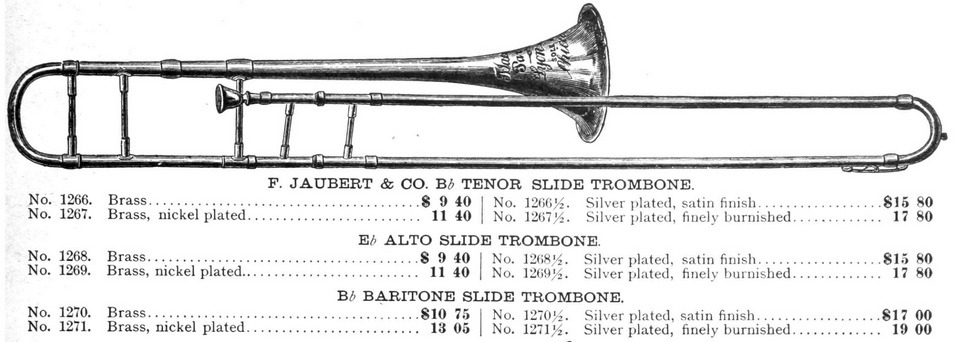

The “standard” trombone and the instrument with which most students begin, is more correctly called a Tenor Trombone in B flat. Compared to a tuba or a saxophone, the trombone looks a simple thing with just three main parts: a mouthpiece at one end, a flared bell at the other and a sliding tube in between. Strictly speaking, the slide is composed of two parallel, stationary inner tubes and two movable outer tubes. The trombone might look like a simple instrument but appearances can be deceptive and it is quite a challenge to play to a decent standard. The co-called B flat/F tenor trombone, has extra tubing at the “top” end of the instrument which enables the player to reach additional lower notes. There’s a whole family of trombones as well as the tenor. A bass trombone appears in most orchestras, but there are also alto trombones, soprano trombones, baritone trombones, contrabass trombones and piccolo trombones. These exotic instruments are rarely encountered and probably only come out after dark. Some have disappeared completely from the musical world and exist only in museums. However, they all work in the same way.

Brass instruments produce different notes by adding extra lengths of tubing, thus lowering the pitch. While trumpets and tubas use valves to send the air-stream through additional bits of tubing, the trombone uses the slide to make the tube longer. The sound is produced when the player’s lips vibrate against a mouthpiece, causing the air inside the tube to vibrate producing a sound. Not just one sound you understand, but a series of sounds, known technically as the harmonic series. When the slide is in the “closed” position, the player can produce a series of between five and seven different notes of the harmonic series of B flat, simply by changing the lip tension. If the player extends the tube from the “closed” position about 3 inches, a second series of notes can be produced half-a-tone lower.

Another three inches or so, and the pitch drops another half-tone. There are seven slide positions thus providing to a wide range of notes. These positions are not physically marked on the instrument: the player must remember them. If you want to know exactly how it all works, ask a professional trombone player who will be delighted to keep you entertained for several hours with the technical explanations.

The word “trombone” has nothing to do with bones. It derives from the Italian tromba (“trumpet”) and one (an Italian suffix meaning “large”), so the name literally means “large trumpet”. This is something of a misnomer of course. The instrument first appeared during the middle of the 15th century and was to become used extensively all over Europe. It was possibly a development of an instrument known as the slide trumpet. At the time, the trombone was known in France as the saqueboute or the Elizabethan-sounding “sackbut” in English. The name evidently comes from the old French words meaning “to pull” and “to push”.

The sackbut was used mainly outdoors and in church music, in which it usually doubled the voice parts. Trumpet and sackbut players were employed in many German cities to stand watch in the city towers and play fanfares to herald the arrival of important visitors. The sackbut gradually evolved into the modern trombone through several design changes, including an increase in bell flare but the instrument was slow to find a permanent place in the orchestra. Mozart used trombones in a limited number of his works, notably in the opera Don Giovanni and the Requiem.

Beethoven used trombones only in his Fifth, Sixth and Ninth Symphonies. By the middle of the 19th century, the trombone had become standard in the symphony orchestra and many later nineteenth century composers were drawn to the majestic sound of three trombones playing together. With the addition of a tuba, the heroic sound was irresistible. Both Rossini and Wagner were skilled in using the low brasses trombone to dramatic effect. The magnificent sound of the low brass playing the theme in the closing section of Wagner’s Tannhäuser overture is something you rarely forget.

The trombone was welcomed into early jazz bands from military bands. In the early days of New Orleans jazz, the players marched through the streets or were hauled along in an open trailer. The trombone slide got in the way of everyone else and so the player usually sat at the back of the trailer, gaining the nickname tailgate trombone.

Jazz trombonists, especially Edward “Kid” Ory introduced many novel effects including the sliding effect known as the glissando. As Alex Ross wrote, “The sound of an instrument or a voice sliding from one note to another has an ambiguous effect: depending on the context, it can suggest jazzy liberation, wartime destruction, otherworldly realms or primitive rituals.” There are some notable examples of the trombone glissando in 20th century orchestral music, but it seems to have fallen out of use. The effect has become something of a musical cliché.

Ferdinand David (1810-1873): Concertino for Trombone and Orchestra. Roberto de la Guía (trb); Wuppertal Symphony Orchestra cond. Patrick Hahn. (Duration: 15:17; Video: 1080p (HD)

A concertino is the name for a relatively short concerto and not to be confused with a concertina, which is different animal altogether. A concertina is a small free-reed musical instrument with bellows; a simplified version of the accordion and played by people who really should know better.

This work brings together three distinguished names from the 19th century, the composers Felix Mendelssohn and Ferdinand David and the trombonist Karl Traugott Queisser. They were all life-long friends and even finished up working in the same orchestra together: the renowned Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. This was established in 1781 and remarkably, still exists to this day though not with the same players. Oddly enough, Ferdinand David was born in the same house in Hamburg where Felix Mendelssohn had been born the previous year. Ferdinand David was a violinist, and being a pupil of the legendary Louis Spohr, a rather distinguished one at that.

In 1835, Felix Mendelssohn became the music director of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and rejoiced in the somewhat grandiose title of Gewandhauskapellmeister. The same year, Ferdinand David was appointed leader of the orchestra. He not only provided technical advice to Mendelssohn during the preparation of the famous Violin Concerto in E minor but was also the soloist at the premiere. The principal trombonist of the Gewandhaus Orchestra was Karl Traugott Queisser who was well-known throughout Germany. Mendelssohn was so impressed with Queisser that he promised to write him a concerto. However, the composer was so busy with other activities that he had to persuade Ferdinand David to take on the task.

Ferdinand David was already established as a composer: he’d completed about fifty works including five violin concertos. He finished the Concertino for Trombone and Orchestra in 1837 and it was premiered at the Gewandhaus with Queisser playing the solo trombone part and Mendelssohn conducting. It was a brilliant success and has become David’s most popular work. This three-movement concerto contains many hints of Beethoven. It’s a lovely work, full of melodic invention and a brilliant trombone part which calls for exceptional technical skills. The yearning second movement takes the form of a funeral march. The composer must have held it in high regard, because he later arranged it for violin and piano and the arrangement was subsequently performed at his own funeral. Soloist Roberto de la Guía has been with the Wuppertal Symphony Orchestra since 2022. He began his musical studies in Spain at the age of eight and years later completed his student years studying in Freiburg. He has a commanding tone quality but can also play with delightful lyrical touches.

Nino Rota (1911-1979): Trombone Concerto. Kris Garfitt (trb); Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra cond. Oscar Jockel (Duration: 14:59; Video: 1080p HD)

Giovanni “Nino” Rota Rinaldi was an Italian composer, pianist and conductor, best known for his film scores and especially for the films of Federico Fellini and Luchino Visconti. He also composed the music for two of Franco Zeffirelli’s Shakespeare screen adaptations and for the first two parts of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather trilogy. He wrote more than 150 film scores in total. That would be more than enough for most composers, but Rota also found time to compose ten operas, five ballets and dozens of other orchestral, choral and chamber works.

The three-movement Concerto for Trombone and Orchestra in C dates from 1966 and was premiered three years later in Milan by the trombonist Bruno Ferrari. It’s become one of the important trombone concertos in the classical repertoire. The work has light, transparent orchestration and uses a relatively small string section, minimal woodwind and a brass section consisting of only two horns. It launches off with fanfare-like figures from the soloist, with large melodic leaps, itself something of a challenge to a brass player. It’s catchy, attractive music that falls easily on the ear. The moody second movement with its dark, repeated chords develops into a haunting melody for the soloist over a chugging accompaniment from the strings. The last movement scampers along merrily with superbly articulated playing from soloist Kris Garfitt who has won many international prizes for his fine playing. He produces a wonderful, luminous tone quality on the instrument and he performs frequently with many of Europe’s leading orchestras. This is a rewarding work for the listener and an excellent taster of Nino Roti’s concert music.