What’s the first thing that comes into your mind if I mention the name “Mexico”? Perhaps you get images of sombreros, giant cacti or chihuahuas. Or maybe tacos, chocolate, salsa, margaritas, tequila or mariachi bands spring to mind. The culturally aware might have visions of the great archaeological sites and their impressive pyramids. Even if you have more than a passing interest in the arts, you probably don’t readily associate Mexico with classical music. It’s a curious thing, but in Europe – and even more so in Asia – we rarely hear the name “Mexico” and the expression “classical music” in the same sentence.

A great deal of Mexican orchestral music just doesn’t seem to have caught on in other parts of the world. This is not because there’s anything wrong with it, but I suspect that many European concert promoters are reluctant to programme the music of lesser-known composers when other names such as Beethoven, Brahms and Tchaikovsky are far more likely to put bottoms on concert hall seats. This is a shame, for much of Mexico’s orchestral music is often as colorful and joyful as the country’s dozens of mariachi bands. Not surprising really, because many Mexican composers have turned to the folk music of their own country for ideas and inspiration, as indeed did many European composers before them, notably Grieg, Sibelius and Dvorak.

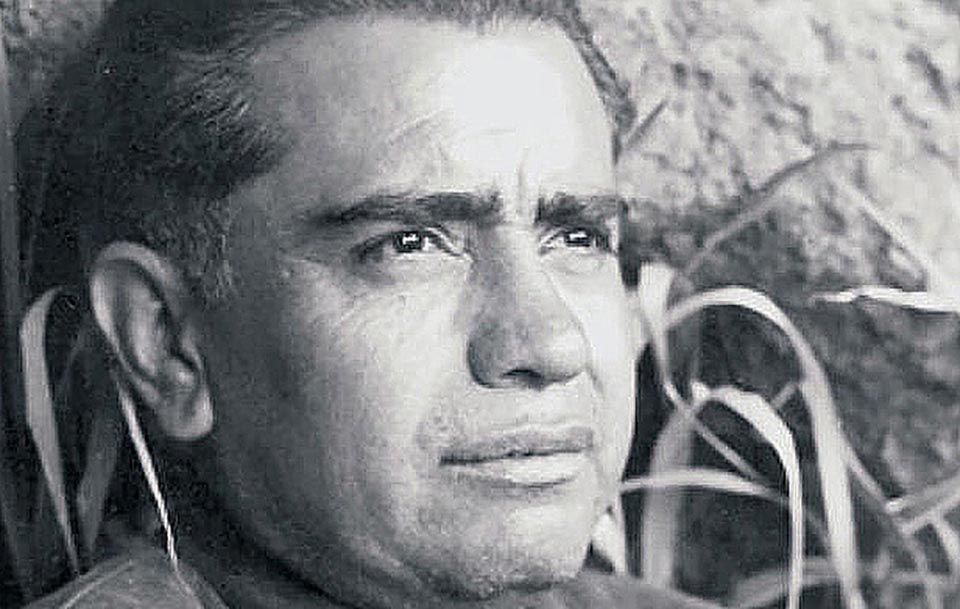

The three top names we need to remember are those of Carlos Chávez (often considered the grandfather of modern Mexican orchestral music), Silvestre Revueltas and José Pablo Moncayo often known by his full name José Pablo Moncayo García. The American musicologist Dr. Robert Olson wrote “As a composer, Moncayo represents one of the most important legacies of Mexican nationalism.” This is despite the fact that today he is remembered for only one work.

That one work is his 1941 orchestral piece Huapango, which is based on a traditional Mexican dance still performed today on city streets in Mexico. These traditional dances, usually accompanied by singer, guitars and violin are tremendously exciting to hear. And Huapango is a wonderful work, full of elation and joy. Hearing street musicians perform a huapango, you can hear exactly where Moncayo got his ideas and how well he transferred them to symphony orchestra. One problem with transcribing a huapango is that the musicians never sing the same melody twice in the same way. If you haven’t come across this work, there’s an excellent video on YouTube given by the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra. But let’s look at something far less well known, yet equally evocative of the sounds and atmosphere of Mexico.

In 1929, at the age of seventeen Moncayo was admitted to the Conservatorio Nacional de Música in Mexico City. To pay for his studies, he worked in various bars and restaurants as a jazz pianist. The Sinfonietta (it literally means “little symphony”) was written during the composer’s residence at the Tanglewood Festival in 1942 in response to a competition organized by the Symphony Orchestra of Mexico with the intention of stimulating new national works. Moncayo wrote the work under the pseudonym “Mundo” and the piece won the first prize. It was premiered in 1944 by the Mexico Symphony Orchestra directed by Carlos Chávez but oddly enough, the work was evidently not much appreciated in its home country and was not performed again until 1992.

The Sinfonietta is a surprisingly short work, barely lasting ten minutes. Written in a characteristic Mexican nationalistic style, the movements are played without a break. The first movement, uses classical sonata form though the Mexican flavor dominates, with lyrical melodies, stimulating rhythmic passages and often a dreamy-like atmosphere evoking things of times past. The second movement is a lively scherzo and the slow third movement begins with a horn solo introducing a nostalgic melody, which is then picked up by the orchestra. The last movement begins with an introduction that slowly leads us to a faster section which drives the piece to an exhilarating conclusion. In the music, you might even hear echoes of Aaron Copland, with whom Moncayo studied at the Tanglewood Music Festival. Incidentally, while working at the Festival, Moncayo met Leonard Bernstein about whom he modestly remarked, “was kilometers ahead of me.”

The Sinfonietta is full of lively music and typical of the composers’ national style, despite the fact that the work lay silent for almost fifty years. And in case you’re wondering, the Metropolitan Youth Symphony is youth orchestra organization in Portland, Oregon, which serves educate, develop and promote young musicians. It provides music education and performance opportunities for young musicians of all ages and levels of experience. Now approaching its fiftieth year, the organization enrolls over five hundred young musicians annually from the local areas and provides a wide variety of musical opportunities. Their orchestra certainly gives a spirited performance of this splendid work.

|

|

|