We learn from history that we learn nothing from history. – George Bernard Shaw

Dutch disease

Dutch disease is a term coined by The Economist in the late 1970s.1 It describes the economic effects which resulted from the discovery of huge natural gas resources in Dutch waters of the North Sea in 1959. In the years after the gas deposits were discovered, the newfound wealth caused the currency (the guilder) to strengthen, making exports of all Dutch products other than oil to become less competitive on world markets. Not only that, but the influx of imports into the Netherlands rose dramatically.

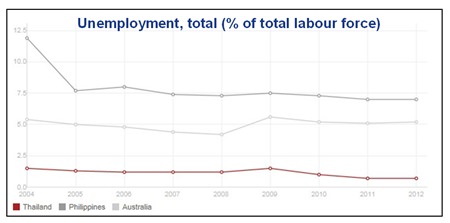

Chart 1 – Sources: ILO & World Bank

Chart 1 – Sources: ILO & World Bank

A similar pattern occurred in Great Britain a decade later,2 when the price of oil quadrupled and it became commercially viable to drill oil off the coast of Scotland, once again in the North Sea. Suddenly, from being a net importer, Britain became a net exporter of oil. The pound’s value soared and the economy went into recession as British-made products became expensive to buy overseas and there were demands for higher wages at home.

Thailand

It could be argued that right now Thailand is suffering from some kind of economic disease. It may not be totally Dutch in character but its consequences restrict the opportunities for a healthy economy. The details are different – Thailand is the second largest net oil importer in Southeast Asia behind Singapore, for example.3

However, the country has an abundance of natural resources – something it has enjoyed throughout history. This has meant that its agricultural sector has traditionally been strong. Added to that is the relatively recent phenomenon of a strong manufacturing sector: in 2013, Thailand was the world’s ninth largest producer of motor vehicles4, for example. In terms of exports, in 2013, machinery represented 42% of Thailand’s exports, manufactured good 13% and food a further 12%.

The upside to Thailand’s specialisation in labour-intensive industries is that, when compared to other countries, it enjoys a constantly low rate of unemployment – at the end of September 2014, Thailand’s unemployment rate stood at just 0.8% (see chart 1).

The downside, however, is that these sectors are highly price-sensitive sectors when compared to others, such as services. Therefore, monthly wages remain low relative to Malaysia, let alone Singapore (see chart 2).

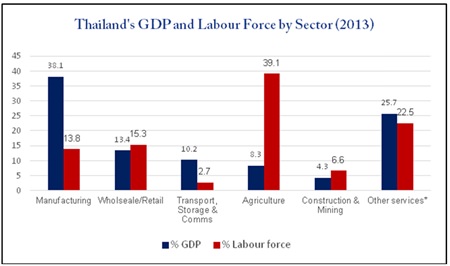

Chart 2

Proof of this is that in 2013, Agriculture employed just over 39% of the country’s workers, yet it only produced a little over 8% of the GDP. Manufacturing faired extremely well, using just under 14% of the work force to create 38% of the GDP; yet history has shown us that once wages increase significantly in a country, manufacturing often moves to somewhere cheaper (see chart 3).5

Chart 3 – Source: Bank of Thailand

Chart 3 – Source: Bank of Thailand

This highly-resourced, low-salaried, low unemployment scenario feeds into the economic dominance of a small number of families, who own businesses in many different sectors. It could be argued that this is merely a continuation of Thailand’s rentier system with the lower income band maintaining allegiances to their employers.

Whatever the reasons, it is curious to see that, unlike others – Filipinos in particular – Thai people do not generally leave the country in search of a better standard of living. The latest figures6 show that there are 130,500 Thais working overseas; as opposed to 10.5 million Filipinos. In fact, only 1.5% of Thailand’s GDP comes from Thais sending money home; this compares meekly with The Philippines’ figure of 9.8%.

So the overall picture we see is of Thai people staying at home, content with the chance to work, even though the job may not be well paid. Of course, this is only as accurate as any generalisation can be. A much larger percentage of Thai students go abroad to study than Filipinos, for example. However, that number is still only 0.07%7 of all students and, judging by the fact that 30% of these study in the US and 25% in the UK, it appears limited to young people from wealthy families.

Some countries have managed to break out of such a situation through entrepreneurship. Back in the 17th century, for example, farmers in southern Germany’s Black Forest would supplement their income in the long winter months by making cuckoo clocks8, starting an industry that has become world famous.

Not only are there no long, unfruitful winter months in Thailand; there is also a lack of entrepreneurship. Despite the World Bank and various governments’ push to improve skills9, the reality is that the cost and bureaucracy involved in starting a business in Thailand can be off-putting. The International Entrepreneurship website suggests there are several obstacles:10

“Entrepreneurship in Thailand is hampered due to ineffective enterprise education and a lack of qualified management. […] Bureaucratic red tape has prevented some entrepreneurs from starting businesses in Thailand. […] Protection of Intellectual property rights remains an issue in Thailand.”

One entrepreneur is more direct, “Want to be a successful start-up? Settle in Thailand, but register your company elsewhere.”11

The possibilities for change

It is clear that for Thailand to achieve its economic potential it must break the cycle. Not only that, it must do so quickly.

In 2013, just under 10% of Thailand’s exports went to the EU – about the same percentage as that destined for the US. However, by the end of 2014, Thailand will no longer be eligible to benefit from the EU’s Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) privileges.

This is because, ironically, under EU norms, Thailand is now considered an upper-middle income country. Thai exports will therefore lose competitiveness to countries that still receive the GSP privileges (e.g. India, Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines).

One way out of this would normally be to establish a free-trade agreement with the EU, as Malaysia has done. Negotiations with the EU are in fact ongoing but are unlikely to be completed until 2017 and ratification can only take place once Thailand has an elected government.12

Thus Thailand needs to change internally. There are four keys needed to break the cycle: an easier and cheaper process to set up SMEs; access to start-up capital; investment in infrastructure; and to translate education system into a skilled workforce.

Since the government took power in May, it has gone ahead with a scaled-down version of the previously published infrastructure plan, by approving THB 3.3 bn for 18 projects13. It also seems to be listening to calls for a simpler business start-up procedure, as well as promoting the use and domestic production of renewable energy.14

Of course the question remains that, even with its ability to push through reforms which governments with outside interests cannot, will the government be able to deliver the necessary changes and cure the disease?

Footnotes:

1 http://www.economist.com/node/16964094

2 http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2010/wp10103.pdf

3 EIA Report (2013) http://www.eia.gov/countries/cab.cfm?fips=TH

4 OICA http://www.oica.net/category/production-statistics/

5 Bank of Thailand

6 Bank of Thailand (2013) & Commission on Overseas Filipinos (2012)

7 UNESCO Institute of Statistics

8 https://www.thewellmadeclock.com/category/the-black-forest/

9 World Bank (2012), Thailand: Innovation and Skills will Generate More Jobs

10 Entrepreneurship in Thailand, International Entrepreneurship, www.internationalentrepreneurship.com/asia/thailand/

11 Saiyai Sakawee, Tech in Asia, April 18, 2014

12 http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2014/10/24/infrastructure-spending-is-the-medicine-thailands-insecure-economy-really-needs/

13 http://www.bangkokpost.com/business/news/454391/key-challenges-for-2015

14 http://thainews.prd.go.th/centerweb/newsen/NewsDetail?NT01_NewsID=WNECO5706270010004

| Please Note: While every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is correct, MBMG Group cannot be held responsible for any errors that may occur. The views of the contributors may not necessarily reflect the house view of MBMG Group. Views and opinions expressed herein may change with market conditions and should not be used in isolation. MBMG Group is an advisory firm that assists expatriates and locals within the South East Asia Region with services ranging from Investment Advisory, Personal Advisory, Tax Advisory, Corporate Advisory, Insurance Services, Accounting & Auditing Services, Legal Services, Estate Planning and Property Solutions. For more information: Tel: +66 2665 2536; e-mail: [email protected]; Linkedin: MBMG Group; Twitter: @MBMGIntl; Facebook: /MBMGGroup |